- by New Deal democrat

The August jobs report was the mirror image of most earlier reports this year: a lackluster Establishment report but a strong Household report. Let’s take a look.

By now the fact that there has been a jobs slowdown is pretty well established. In the last 7 months, only 964,000 jobs have been added, an average of 138,000 per month. If we subtract this month’s temporary census hiring of 25,000, those numbers drop to 939,000 and 134,000, respectively:

And keep in mind that the number of jobs added between March 2018 and March 2019 is going to be reduced from roughly 210,000 to 167,000 per month.

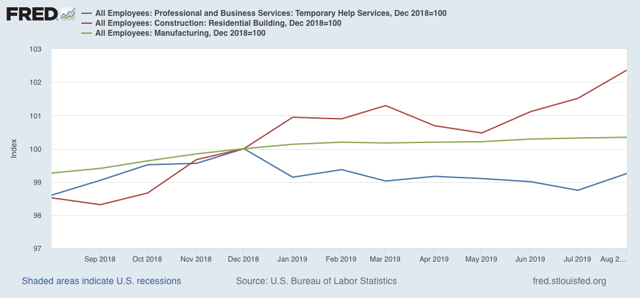

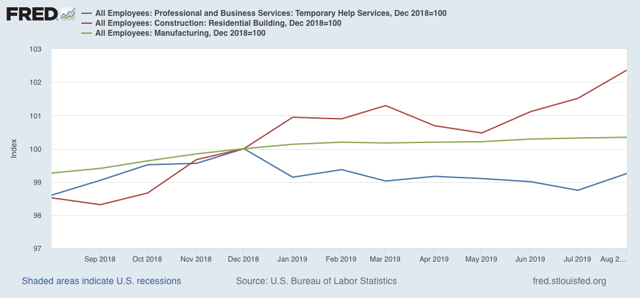

Since last December, of the leading employment sectors, only residential construction has continued to increase significantly. Manufacturing has added only 19,000 jobs in the last 6 months, and temporary jobs have actually declined since the end of last year:

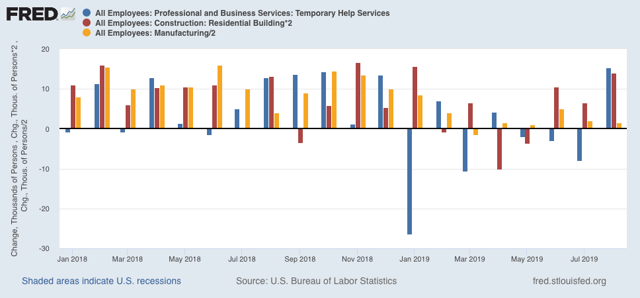

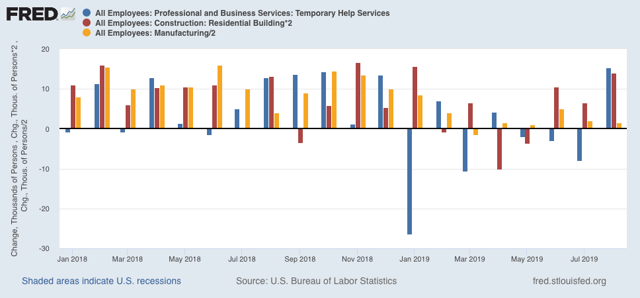

Here’s what the month to month breakdown of all three leading sectors looks like compared with 2018, showing the slowdown this year - except, so far, for this past month:

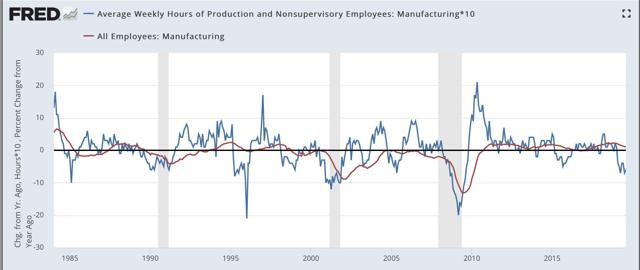

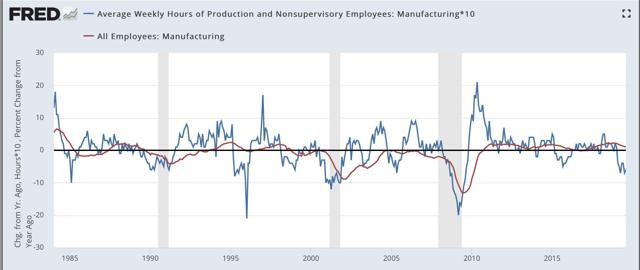

Further, because even with August’s increase, the average manufacturing workweek is down almost 1 full hour per week YoY (blue in the graph below), we should expect actual losses in manufacturing jobs going forward:

Before 1980, manufacturing jobs’ growth or decline typically followed hours by roughly 2 months. Since then, the time period has lengthened to more like 6 months.

That being said, if a similar pattern is followed to what happened in 2016, by the end of next spring, we should expect *no* net YoY in manufacturing jobs, which means a decline of at least -25,000 jobs during roughly the next 9 months.

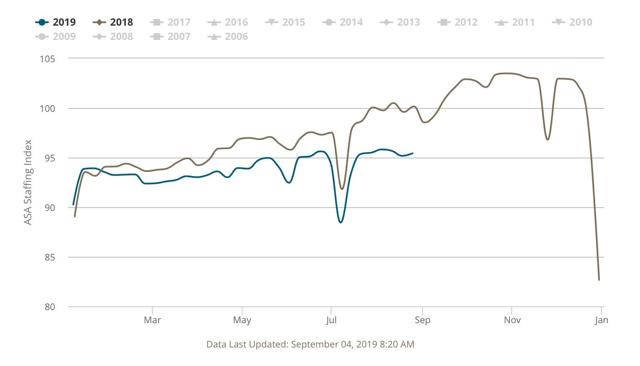

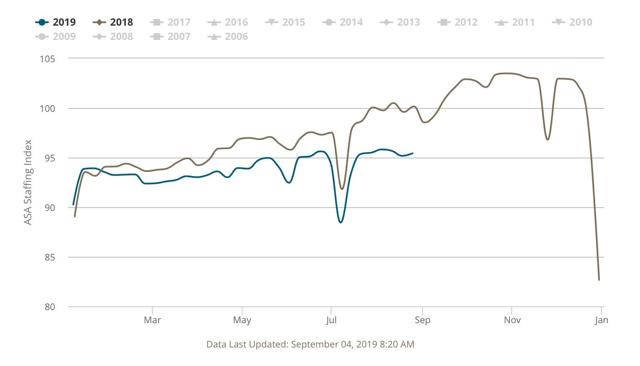

On a similarly granular level, it seems that each month in my jobs report write-up, I comment on a surprising *increase* in temp jobs, despite the worsening YoY decline in the American Staffing Association’s temporary jobs Index:

And yet, as you can see from the graphs above, temporary jobs have indeed declined this year. So I went back and compared the original numbers for temporary jobs in each jobs report this year (1st column) with the final number (2nd column), and as I suspected, the revisions have been very asymmetrical:

JAN +1500 -26,300

FEB +5800 +7000

MAR -5400 -10,500

APR +17,900 +4300

MAY +5100 -2000

JUN +4300 -2900

JUL +2200 -7300*

AUG +15,400 ——

*1st revision only

As originally reported, every single month this year except for March was positive. But as finally revised, only two months have been positive so far. Given the worsening comparisons in the Staffing Association’s Index in August, I would be very surprised if the initial rosy number for temporary jobs in August’s jobs report holds up. Needless to say, this is the kind of thing that happens at turning points.

Stepping back a bit to look at the goods-producing sector overall, this has also slowed down considerably, adding only 73,000 jobs in total since January, or 10,000 per month:

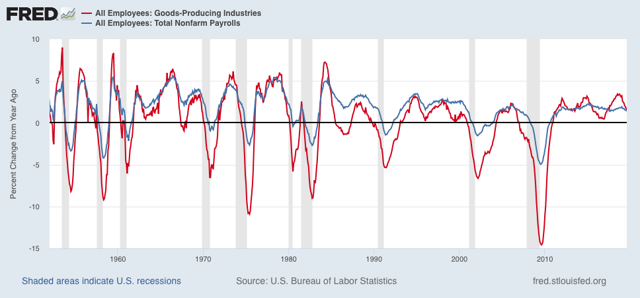

As shown in the graph below, goods producing jobs (red) are much more pro-cyclical compared with jobs overall (blue):

By now the fact that there has been a jobs slowdown is pretty well established. In the last 7 months, only 964,000 jobs have been added, an average of 138,000 per month. If we subtract this month’s temporary census hiring of 25,000, those numbers drop to 939,000 and 134,000, respectively:

And keep in mind that the number of jobs added between March 2018 and March 2019 is going to be reduced from roughly 210,000 to 167,000 per month.

Since last December, of the leading employment sectors, only residential construction has continued to increase significantly. Manufacturing has added only 19,000 jobs in the last 6 months, and temporary jobs have actually declined since the end of last year:

Here’s what the month to month breakdown of all three leading sectors looks like compared with 2018, showing the slowdown this year - except, so far, for this past month:

Further, because even with August’s increase, the average manufacturing workweek is down almost 1 full hour per week YoY (blue in the graph below), we should expect actual losses in manufacturing jobs going forward:

Before 1980, manufacturing jobs’ growth or decline typically followed hours by roughly 2 months. Since then, the time period has lengthened to more like 6 months.

That being said, if a similar pattern is followed to what happened in 2016, by the end of next spring, we should expect *no* net YoY in manufacturing jobs, which means a decline of at least -25,000 jobs during roughly the next 9 months.

On a similarly granular level, it seems that each month in my jobs report write-up, I comment on a surprising *increase* in temp jobs, despite the worsening YoY decline in the American Staffing Association’s temporary jobs Index:

And yet, as you can see from the graphs above, temporary jobs have indeed declined this year. So I went back and compared the original numbers for temporary jobs in each jobs report this year (1st column) with the final number (2nd column), and as I suspected, the revisions have been very asymmetrical:

JAN +1500 -26,300

FEB +5800 +7000

MAR -5400 -10,500

APR +17,900 +4300

MAY +5100 -2000

JUN +4300 -2900

JUL +2200 -7300*

AUG +15,400 ——

*1st revision only

As originally reported, every single month this year except for March was positive. But as finally revised, only two months have been positive so far. Given the worsening comparisons in the Staffing Association’s Index in August, I would be very surprised if the initial rosy number for temporary jobs in August’s jobs report holds up. Needless to say, this is the kind of thing that happens at turning points.

Stepping back a bit to look at the goods-producing sector overall, this has also slowed down considerably, adding only 73,000 jobs in total since January, or 10,000 per month:

As shown in the graph below, goods producing jobs (red) are much more pro-cyclical compared with jobs overall (blue):

There have been YoY losses in goods-producing jobs before all of the past 3 recessions, and going back 70 years, counting 12 recessions, in all but 3 there has been steep deceleration before and actual losses no later than two months into the recession. We’re not quite there yet.

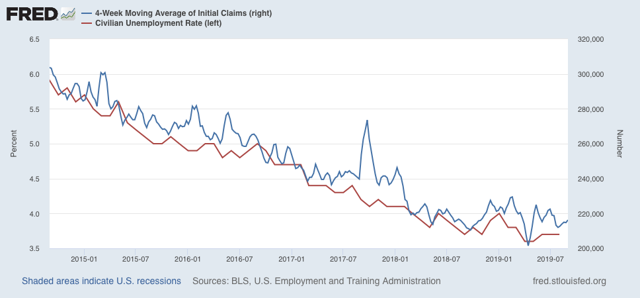

Turning to unemployment, labor force participation, and wages, let’s update the graph of how initial jobless claims slightly lead the unemployment rate:

Initial jobless claims have trended only slightly lower in the past 18 months, and are flat over the past 12. The unemployment rate has continued to trend slightly lower, but I expect that to end in the next several months, with no new lows, and more likely a drift sideways at 3.7% or even slightly higher to 3.8% or even 3.9%.

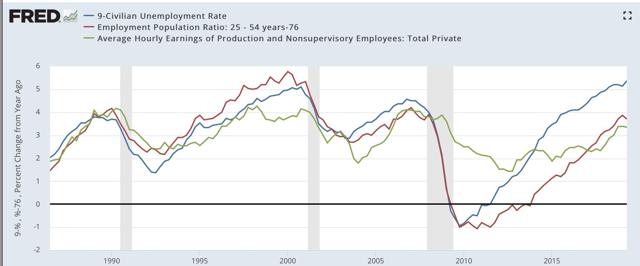

Finally, in the past 30 years, the unemployment rate has tended to start declining after recessions before the prime age employment to population ratio improves, and that in turn has turned higher before YoY wage growth finally turns higher (note: averaged quarterly to cut down on noise; unemployment rate inverted):

Similarly, at recent peaks, the unemployment rate may slightly lead prime age employment, which in turn declines before YoY wage growth does.

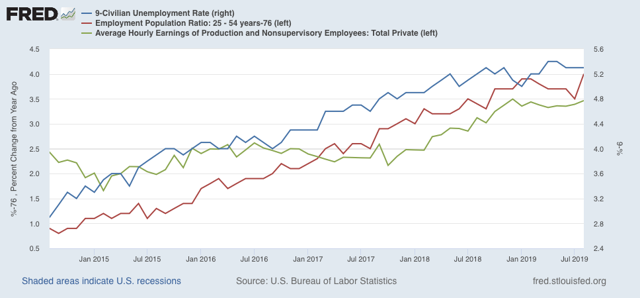

As the below close-up of recent monthly changes shows, gains in both the unemployment rate and the prime age participation rate seem to be slowing overall, and this year wage growth has as well:

We should expect the unemployment rate to turn up, and the E/P ratio to turn down, several months before any recession. Wage growth is a lagging indicator, however, and only turns up well into expansions, and can continue right into the next recession.