- by New Deal democrat

At the beginning of this year, I identified graphs of 5 aspects of the economy that most bore watching. Now that we have the data for the first 1/3 of the year, let's take a look at each of them.

#5 The Yield Curve

The Fed having embarked on a tightening regimen as of December, the question is, will the yield curve compress or, worse, invert, an inversion being a nearly infallible sign of a recession to come in about 12 months.

Here's what has happened so far:

Rates on 2 year treasuries rose in advance of the Fed's move in November, but have since fallen to their pre-December range, while the 10 year treasury yield has continued to decline at a slow rate (typically long rates only start to fall once the tightening cycle has caused the economy to weaken). At 0.99% as of last Friday, however, the yield curve is still quite positive when seen in a historical perspective.

Rates on 2 year treasuries rose in advance of the Fed's move in November, but have since fallen to their pre-December range, while the 10 year treasury yield has continued to decline at a slow rate (typically long rates only start to fall once the tightening cycle has caused the economy to weaken). At 0.99% as of last Friday, however, the yield curve is still quite positive when seen in a historical perspective.

Weakness in the economy has put the Fed back on hold, but if the trend in rates were continue, then even as few as two more .25% rate hikes by the Fed could cause the yield curve to invert.

#4 The trade weighted US$

#4 The trade weighted US$

Perhaps the biggest story of 2015 was the damage done by the 15%+ surge in the US$ that began in late 2014 -- which not only harmed exports, but pretty much cancelled out the positive effect on consumers' wallets by lower gas prices.

Here there has been a big change:

Against all currencies, the US$ has recently ben in the range of +3% to +5% YoY - a more typical range. Against major currencies, the US$ has actually declined YoY. This is good news.

Against all currencies, the US$ has recently ben in the range of +3% to +5% YoY - a more typical range. Against major currencies, the US$ has actually declined YoY. This is good news.

#3 The inventory to sales ratio

An elevated ratio of business inventories to sales means that businesses are overstocked. This has frequently but not always been associated with a recession. I have been using the wholesalers invenotry to sales ratio, since it has fewer secular issues. Here the news has not good this year, as the raito increased in January, although it fell ever so slightly in February and March:

This is probably the single worst statistic in the economy right now.

This is probably the single worst statistic in the economy right now.

#2 Discouraged workers

While 2015 saw a big improvement in involuntary part time employment, the number of those so discouraged that they did not even look for work, even though they want a job, went stubbornly sideways until the last quarter of 2015. Although it has not borken through its December low, and is still above its rate in the later part of the 1990s through 2007, in the first 4 months of this year, the trend has clearly been down:

This looks like improvement, but we are still at least 500,000 above a "good" number.

This looks like improvement, but we are still at least 500,000 above a "good" number.

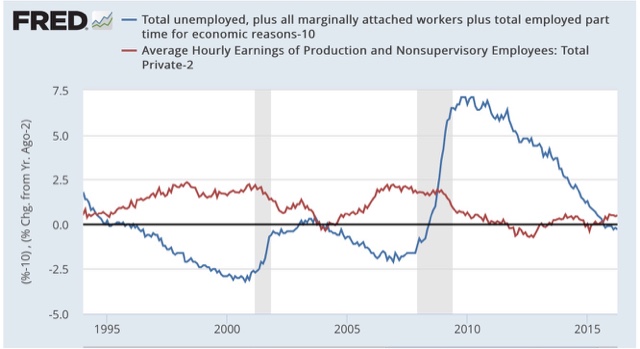

#1 Underemployment and wages

The single worst part of this economic expansion has been its pathetic record for wage increases. Nominal YoY wage increases for nonsupervisory workers were generally about 4% in the 1990s, and even in the latter part of the early 2000s expansion. In this expansion, however, nominal increases have averaged a pitiful 2%, meaning that even a mild uptick in inflation is enough to cause a real decrease in middle and working class purchasing power.

There is increasing consensus that the primary reason for this miserable situation has been the persistent huge percentage of those who are either unemployed or underemployed, such as involuntary part time workers.

The single worst part of this economic expansion has been its pathetic record for wage increases. Nominal YoY wage increases for nonsupervisory workers were generally about 4% in the 1990s, and even in the latter part of the early 2000s expansion. In this expansion, however, nominal increases have averaged a pitiful 2%, meaning that even a mild uptick in inflation is enough to cause a real decrease in middle and working class purchasing power.

There is increasing consensus that the primary reason for this miserable situation has been the persistent huge percentage of those who are either unemployed or underemployed, such as involuntary part time workers.

This expanded "U6" unemployment rate ( minus 10%) is shown in blue in the graph below, toether with YoY nominal wage growth (minus 2%)!:

In the 1990s and 2000s, once the U6 underemployment rate fell under 10%, nominal wage growth started to accelerate. U6 is now 9.7%, and there has been some mild improvement off the bottom. More than anything, the US needs real wage growth for labor, and the present nominal reading of 2.5% still isn't nearly good enough. With the expansion in deceleration mode past mid-cycle, it is not clear at all how much further improvement we are going to get before the next recession hits.

In the 1990s and 2000s, once the U6 underemployment rate fell under 10%, nominal wage growth started to accelerate. U6 is now 9.7%, and there has been some mild improvement off the bottom. More than anything, the US needs real wage growth for labor, and the present nominal reading of 2.5% still isn't nearly good enough. With the expansion in deceleration mode past mid-cycle, it is not clear at all how much further improvement we are going to get before the next recession hits.