It is very likely that in the next couple of months we will see a positive establishment survey job creation number (the household survey already went positive in January), but it is also likely that those job gains will be small at first and we will need larger and more sustained job creation in order to really get the unemployment rate back down substantially. I am going to paint a somewhat gloomy picture of why we may be in a bind, as many of the jobs lost during the recession are likely not coming back and why the areas that have lead job creation in the recent past (ie services) are also unlikely to pick up the slack.

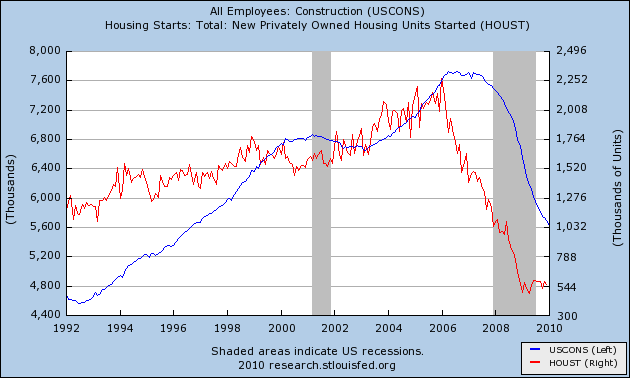

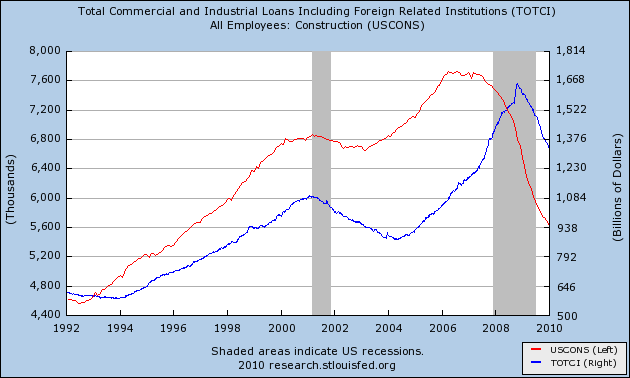

First, let's examine a leading job creator since the early 90's, construction, which nearly doubled its employment level from 1992 to the peak in 2006 (gaining around 3 million jobs). As you can see from the graphs below, construction employment tanked during this recession (right along with housing starts and commercial/industrial lending).

The interesting information we can gain from the second graph is that construction employment may follow commercial/industrial lending even more closely than housing starts (which makes sense because commercial/industrial projects typically employ exponentially more construction workers than houses). The graphs above are bad news for future job creation for two reasons: 1) it is unlikely that housing starts are going to see a v-shaped recovery due to inventory and loan standard issues and 2) commercial/industrial lending has yet to bottom and the days of huge (and expensive) office/retail centers may be numbered due to the internet. In other words, I wouldn't look to construction jobs to lead us out of this recession (or even to recover to their highs for a long time).

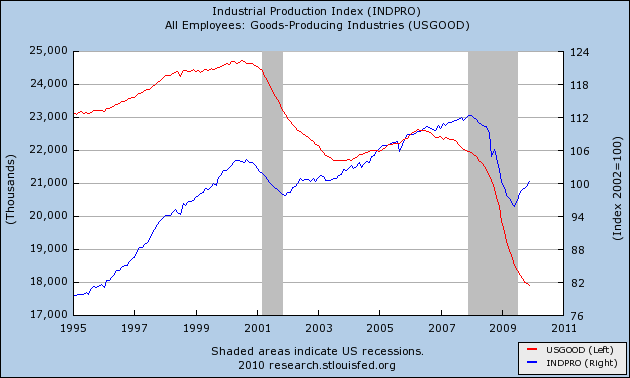

Next, let's look at goods producing employment. While goods producing employment wasn't really a major job creator at all during the last 15 years (actually a lot longer), it was still a major employment sector with 22+ million jobs prior to this recession. Since its peak in late 2006 though, good producing employment has shed over 4 million jobs (or about 20%), while industrial production only fell about 10% during this time frame.

This graph shows the huge decline in goods producing jobs, that is much deeper than the decline in industrial production, but this doesn't even tell the whole story, as demand had declined too, which leads us to:

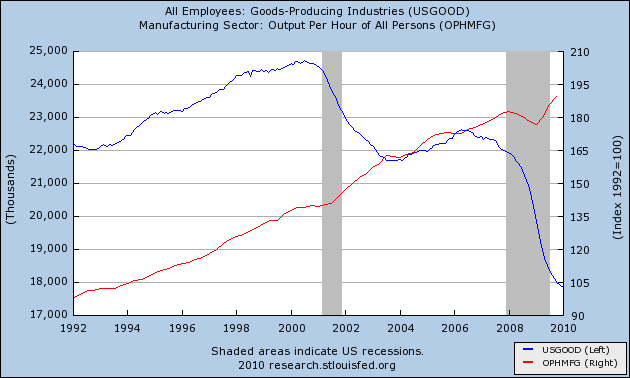

This shows how dramatically the output of those goods producing employees has risen in the recent past and even continuing its rise during this recession (after a brief drop). What this shows us quite clearly is that it is not outsourcing that is taking our manufacturing jobs away, but technology increases that lead directly to productivity gains. I would estimate that the number of jobs lost in manufacturing over the last decade to outsourcing is probably less than a tenth of what has been lost to technology (remember, you read about every plant that closes and goes to China, but none about the plants that replace a few workers here and there with machines or computers). What the first graph of industrial production shows us in quite damning terms is that we are now at 2002 levels of industrial output with 4 million less employees creating that output (and production is rising again). In other words, I wouldn't look to the goods producing sector to lead us in creating jobs soon (and maybe for a very long time).

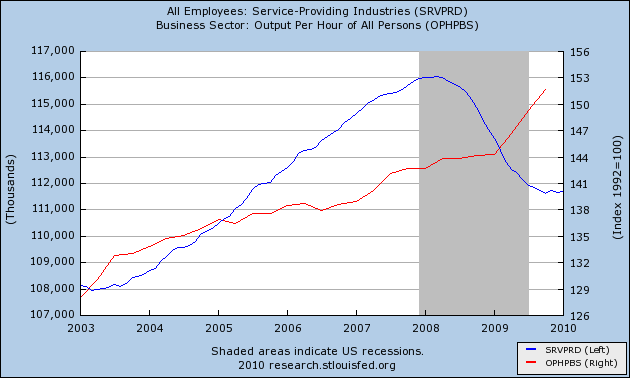

Finally, we have to look at the service sector, which had bee relatively immune (in job creation terms) to recessions in the recent past until now. During this recession services employment has lost over 4 million jobs and while it appears that the losses here have stopped, the output per hour (of the business sector) curve has steepened dramatically (ie the rate of productivity increases has increased).

This could be caused by many factors (including working current employees longer, although the hourly data doesn't back this up), but I believe the biggest reason for this increase is the acceptance/adoption and proliferation of technology to the service sector, something we really haven't seen before en mass. This again bodes poorly for a sudden burst in job creation as technological innovation again outpaces the need to hire new workers.

In conclusion, I fear that we may have reached a point where the creation of jobs in quantities large enough to get our unemployment rate back down to a full employment (say 5-6%) level may be behind us under the current economic paradigm. This would lead me to believe that a Keynesian solution is wrong for our situation (as the extra spending will not lead to job creation, but will be eaten up through productivity) and that the solution to our problem lies more on the policy side of creating a new paradigm that would provide a better safety net for those displaced by technology (ie things like single-payer health care, longer standard unemployment benefits, etc) and by enabling workers to gain the benefits of productivity through shorter work weeks and an increased emphasis on telecommuting.