There's one point that I think is incredibly important right now. I touch on it in the second article, but I'm not the one who presented a detailed analysis of how it happened. That distinction goes to Angry Bear:

Update: Market Watch

Consider the description of the bailout from the: New York Times:

Investors who own the companies’ common and preferred stock will suffer. Holders of debt, including many foreign central banks, are expected to receive government backing. Top executives of both companies will be pushed out, according to those briefed on the plan. [italics mine]

Now consider the following from MarketWatch,

The top five foreign holders of Freddie and Fannie long-term debt are China, Japan, the Cayman Islands, Luxembourg, and Belgium. In total foreign investors hold over $1.3 trillion in these agency bonds, according to the U.S. Treasury's most recent "Report on Foreign Portfolio Holdings of U.S. Securities."

China alone holds $376 billion in bond holdings.

Unless I am misreading something, foreign central banks will be protected, including China's...and the America taxpayer will foot that bill.

Secretary Paulson has been busy of late reassuring foreign central banks that they will be protected.

In recent weeks, Treasury officials have been reaching out to foreign central banks and other overseas buyers of securities or debt sold by the two companies, to reassure them of the creditworthiness of these instruments.

In one such conversation, at the end of August, the Treasury sought to reassure the Bank of Mexico, according to a person familiar with the matter, of the soundness of agency securities held by the bank. Treasury officials have also had similar conversations with Japanese investors who are buyers and holders of agency debt.

.....

The meaning and ramifications of this collapse cannot be unravelled in a single post--or a hundred posts. Mismanagement, corporate greed and excess need examining.

Once again, the U.S. taxpayer will be asked to shoulder another mountain of debt. Once again, the taxpayer has become the prop of last resort as poorly managed entities become too big to fail. How long this can continue is the question.

Everything seems broken. No one seems to be safely in charge. Instead, I imagine public officials--Bernanke and Paulson-- racing frantically from meeting to meeting, making assurances, looking for the next band-aid.

John McCain wants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to shrink so that their size no longer is a threat. Would he say the same thing about Bear Stearns, albeit it is far smaller? Should Bear Stearns not have been allowed to grow so large? How do we shrink such a massive entities? Remember, they hold over $5 trillion in mortgages. Do we hold a fire sale? And would he apply the lobbying rule to other large companies? After all, they now have a heavy hand in writing the regulations that govern them. (The Medicare Part D fiasco is evidence of just how influential the pharmaceuticals were in deciding just what regulations were best for them.) Is it big government that is the problem--or big corporations that run the government?

Obama wants Fannie and Freddie out of the profit-making business. Is America ready for nationalizing such institutions? Is Obama? And could we have afforded a total collapse of Bear Stearns? Can the government simply allow such things to happen if the consequence for the nation is dire?

And how does the next president reassure our foreign creditors that the U.S. will pay its bills?

While we may be dismayed that foreign central banks will receive "government backing," we do not have much choice.

Yu Yongding, former advisor to China's central bank, put the matter bluntly:

``If the U.S. government allows Fannie and Freddie to fail and international investors are not compensated adequately, the consequences will be catastrophic,'' Yu said in e-mailed answers to questions yesterday. ``If it is not the end of the world, it is the end of the current international financial system.''

Foreign central banks have been propping up the U.S. economy:

Foreign central banks have financed the United States to keep their export sectors -- heavily dependent on U.S. consumer spending -- humming. But they now must weigh the benefits of providing the United States with such "vendor financing" against the rising costs of keeping the current system going.

Yu Yongding is not making a threat; he is stating a fact.

If foreign central banks stop financing U.S. debt (there are no free rides), then the U.S. is in a world of hurt. As Brad Setser notes:

...in fact, the economic and financial risks that arise from the U.S. current account deficit (and the resulting dependence on foreign financing) have not been exaggerated. If anything, they have received too little attention -- and are set to grow in the coming years.

Well, "the coming years" may be sooner, not later. For the U.S., the consequences may be immediate inflation as Treasury attempts to makes its offerings more palatable. The dollar will plunge. And these are just for starters.

The party is over. Sorry that most of you working stiffs missed it. Oh, by the way, here's the bill.

As Paul Krugman said:

I used to think that the major issues facing the next president would be how to get out of Iraq and what to do about health care. At this point, however, I suspect that the biggest problem for the next administration will be figuring out which parts of the financial system to bail out, how to pay the cleanup bills and how to explain what it’s doing to an angry public.

Although the American public is not exactly happy with the economy, it has no idea of the depth of the problems. Most people think the government's check writing ability is infinite.

Well, the government is broke and broken.

This has everything to do with foreign central banks and investors (along with some incredibly large US investors like PIMCO) essentially detailing US policy. Note the following statement from today's WSJ:

Mr. Paulson noted that more than $5 trillion of debt and mortgage-backed securities issued by Fannie and Freddie is owned by central banks and other investors world-wide. "Failure of either of them would cause great turmoil in our financial markets here at home and around the globe," Mr. Paulson said.

Paulson has repeatedly cited foreign ownership as a reason for the intervention. But let's back up a bit to see how the current economy is really structured:

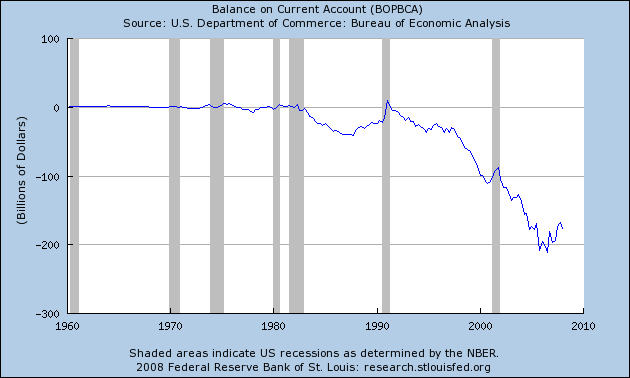

Above is a chart of the current account. All this means is the following: the US buys more stuff from abroad then we sell abroad. The problem is we don't have the money to pay for all of this. Why? Because the US savings rate is terrible:

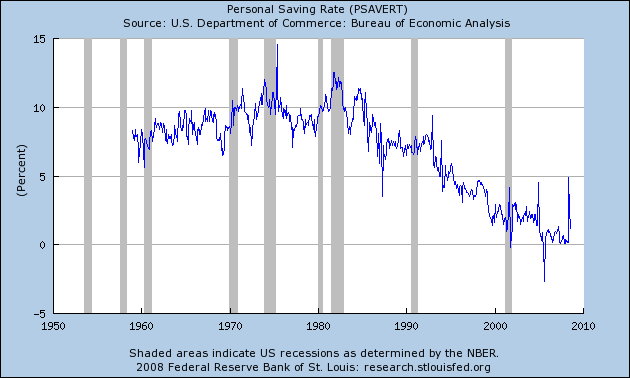

Notice how the US is saving less and less. That means we have to borrow money to buy all of this great stuff.

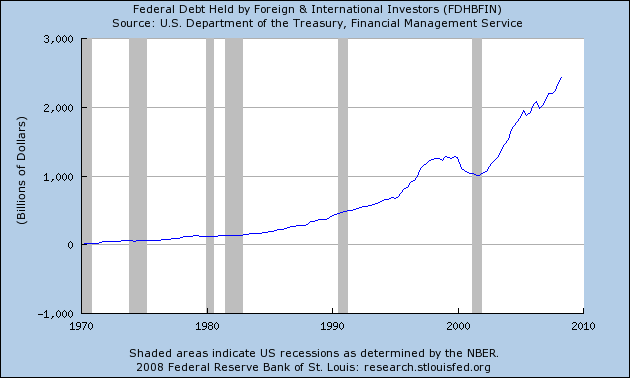

Above is a chart of foreign ownership of US government debt. Notice how it has doubled over the last 8 years. In other words -- we're in debt to foreign central banks up to our eyeballs.

Treasury Secretary Paulson has continually stated that US paper is owned all over the globe. Remember -- Paulson was a big guy at Goldman Sachs. He has contacts all over the world. He knows, well, everybody. Frankly, he's one of the few appointments of the Bush administration that is qualified for his job. When he says "so and so talked to me about this" you can bet it was a conversation between people who have known each other for some time.

The point is all of the press indicates it's these conversations with foreign bankers that got Paulson's attention. That means there are some nervous people all over the globe. And that's what is driving this -- at least partially. And that should scare everyone to death. We are no longer in complete control of our sovereignty.

A long time ago (actually about three years ago) Paul Volcker wrote an editorial in the Washington Post called An Economy on Thin Ice. Consider the following as food for thought:

More recently, we've become more dependent on foreign central banks, particularly in China and Japan and elsewhere in East Asia.

It's all quite comfortable for us. We fill our shops and our garages with goods from abroad, and the competition has been a powerful restraint on our internal prices. It's surely helped keep interest rates exceptionally low despite our vanishing savings and rapid growth.

And it's comfortable for our trading partners and for those supplying the capital. Some, such as China, depend heavily on our expanding domestic markets. And for the most part, the central banks of the emerging world have been willing to hold more and more dollars, which are, after all, the closest thing the world has to a truly international currency.

The difficulty is that this seemingly comfortable pattern can't go on indefinitely. I don't know of any country that has managed to consume and invest 6 percent more than it produces for long. The United States is absorbing about 80 percent of the net flow of international capital. And at some point, both central banks and private institutions will have their fill of dollars.

I don't know whether change will come with a bang or a whimper, whether sooner or later. But as things stand, it is more likely than not that it will be financial crises rather than policy foresight that will force the change.

This editorial seems more and more accurate as time passes.