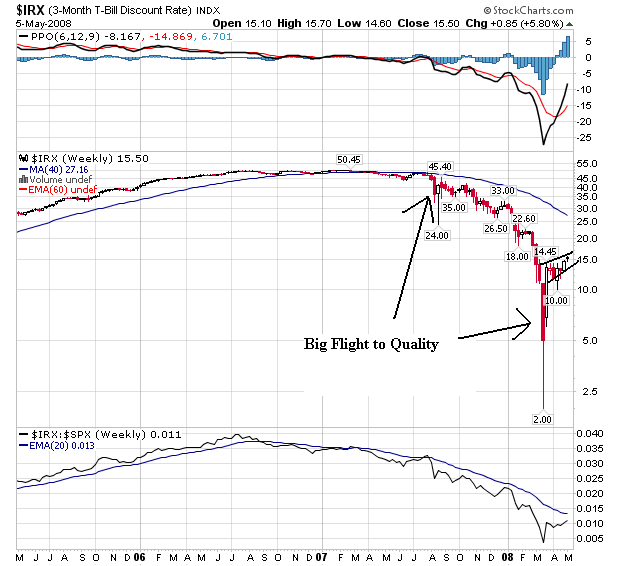

The long-term chart clearly shows the flight to safety that happened as the credit market tightened. Notice how yields dropped big time as this happened. Right now yields have formed a flag pattern as traders wait to see what the next move will be.

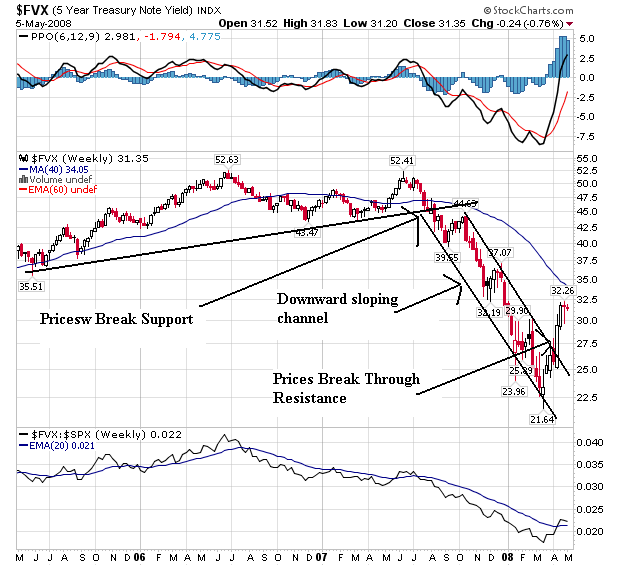

Notice the same thing with the 5-year yields -- they dropped as traders bought the Treasury market in a flight to safety. Also notice how yields have started to move higher.

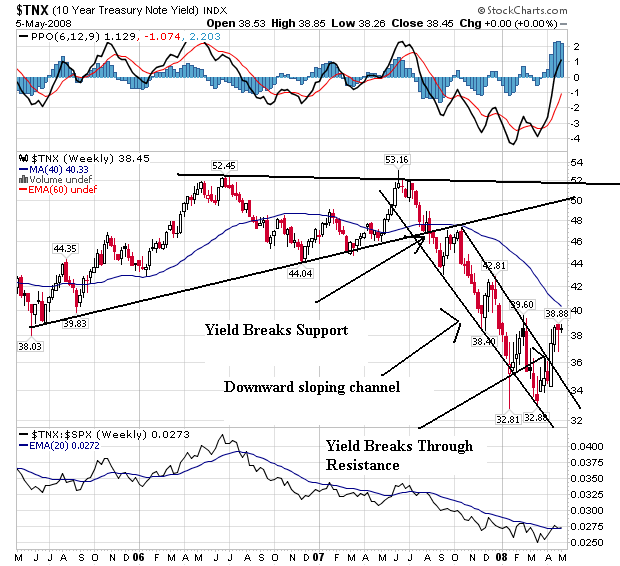

The 10-year Treasury also shows the flight to quality and the subsequent move away from the 10-year. More on this below.

Let's start with the good news. There is growing speculation that moving out of Treasuries and into higher-yielding, risker assets is the standard plan of managers:

Emboldened by economic data signaling a strong likelihood the Federal Reserve will keep rates on hold for now, investors will continue to move into higher-yielding and riskier securities, including corporate and emerging-market debt. Global bond-fund managers may also consider selling short-dated Treasurys and buying government debt of similar maturities in Australia and New Zealand to pick up extra yield.

"That is where the opportunity is: putting on a bet that the fed-funds target rate is going to stay at 2% or lower for a much longer period of time," said James Kauffmann, head of fixed income for ING Investment Management in Atlanta, which oversees more than $40 billion of institutional and mutual-fund assets.

Friday's better-than-expected payrolls report supported the notion that the Fed can retire to the sidelines for now, and government bonds ended sharply lower across the board. But the shift in the market's rate outlook has been under way for several weeks, as the state of the economy has appeared less dire than had been feared. The Fed's liquidity-pumping measures -- which were tweaked again Friday -- have also helped reduce fears of a market meltdown.

Treasuries are also getting competition from a rush of new corporate issues:

On the corporate bond front, U.S. investment-grade companies are likely to issue another $80 billion to $100 billion in new debt in May after a surge of debt offerings in April, Bank of America said in a note released Thursday.

According to Thomson Reuters, companies with high-grade credit ratings issued $117 billion in bonds, the second best month ever. Some $40 billion bonds got underwritten during the week of April 25 alone.

This is a big reason why Treasury yields have moved higher over the last few weeks. Traders have sold Treasuries to move into higher yielding assets and equities. In other words, the flight to safety is starting to ease.

Also adding some upward pressure on yields is the Treasury is trying to figure out how to finance a growing deficit:

As the federal government rolls out its economic-stimulus plan, the Treasury market is eyeing the return of one-year bills and three-year notes to help offset the government's deteriorating fiscal outlook.

Changes to the maturities of debt sold by the government could be announced as early as Wednesday, when the Treasury presents its quarterly refunding program.

But given how low yields currently are on low-risk government debt, these two maturities might be a hard sell.

Yields on Treasurys with maturities of 10 years or less are below the current 4% inflation rate, and returns on government bonds are set to be negative in April for the first time this year.

Remember -- the government is bleeding debt right now. And the latest "stimulus" plan will only make matters worse. Somebody will have to pay for this. And its looking like we're going to ask future generations to pay rather now. At some point, this increased borrowing will lead to higher rates. The question is simply when will that occur.

LIBOR is still an issue indicating that the credit markets are not well.

A major source of stress has been the London interbank offered rate, or Libor, a benchmark for the rates banks pay on dollar loans in the offshore market. It remains unusually high compared with expected Federal Reserve interest rates, an indication that banks continue to hoard dollars.

Central banks have already taken steps to ease European banks' dollar-denominated funding needs, but the resurgent tension has policy makers discussing whether the current arrangements are enough.

There are disagreements about why the rate is rising. Fed officials attribute the recent Libor rise to European banks' needing to borrow in dollars, because the pressure tends to slacken around midday in the U.S. when the European day ends. U.S. banks have tended to retain their dollar holdings until the end of the day in New York, making it even harder for overseas banks to obtain dollars.

European officials aren't convinced demand from European banks for dollars is the source of the trouble. Since March 11, the amount on offer at ECB's swap line has been a relatively modest $30 billion. In each of three $15 billion auctions it has held since then, demand hasn't been overwhelming, suggesting to some European officials that European banks aren't desperate for dollars. The ECB also saw prior global central-bank maneuvers as partly a symbolic effort to try to calm markets.

On Saturday, Barron's outlined the tools the Fed has used in its effort to lower LIBOR:

Libor has remained stubbornly high, at 2.815% for the key three-month maturity. That's higher than it stood before the Fed's previous rate cut, to 2.25% from 3%, on March 18. In other words, the central bank's actions haven't affected much of the real world.

To counter that, the Fed announced it would boost several of its new policy instruments designed to funnel liquidity to the borrowers needing it most. Specifically, the Fed will expand its

Term Auction Facility by 50%, to $75 billion per auction, for a total $150 billion.

The Fed also said it would boost its swap lines to foreign central banks -- to $50 billion from $30 billion for the European Central Bank and to $12 billion, or doubled, for the Swiss National Bank -- to provide the wherewithal for those central banks to lend dollars to banks having difficulty borrowing.

In addition, the Fed said it would expand the collateral accepted at its Term Securities Lending Facility, which allows dealers to swap less-liquid securities for good-as-cash Treasuries, to include triple-A-rate asset-backed securities.