As strains in financial markets eased yesterday, the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan breathed sighs of relief and scaled back their injections of cash into money markets. But they said they remain poised to act again if necessary.

"Money-market conditions are normalizing and...the supply of aggregate liquidity is ample," said the ECB, which has been the most aggressive of the major central banks in trying to keep short-term market interest rates from rising above its target.

...

The Fed and the ECB -- playing the traditional role of central banks as lenders of last resort -- have been responding to an apparent shortage of lendable funds in their markets, exacerbated in part by a widespread reluctance to accept mortgage-backed securities as collateral in the wake of rising defaults on home loans. The spread of complex, hard-to-value securities has complicated matters, increased uncertainty and threatened to make it hard to borrow against good collateral.

Over the last 4-5 trading days we've seen European and American central banks perform the largest cash infusion since 9/11. The reason for the infusions was the price of short-term loans (30 days or less) spiked as banks became more reluctant to make loans to each other. This round appears to be over. However, there are still many questions left.

For example, suppose there is another round of problems at hedge funds, insurers or banks? Right now we simply don't know the extent of subprime ownership. They have spread all over the globe and are held by a variety of institutions (to get an idea for the geographic breadth of the problem go to this interactive FT map). The possibility of a fund announcing major problems right now is still high.

And central banks are faced with a policy dilemma. Under Greenspan, the Fed developed a policy of lowering rates whenever there was a financial crisis. This led to the term Greenspan Put or the less flattering nick-name easy Al. Regardless, Wall Street got used to being bailed out with lower interest rates.

This led to the term moral hazard:

Moral hazard is an old economic concept with its roots in the insurance business. The idea goes like this: If you protect someone too well against an unwanted outcome, that person may behave recklessly. Someone who buys extensive liability insurance for his car may drive too fast because he feels financially protected.

These days, investors and economists use the term to refer to the market's longing for Federal Reserve interest-rate cuts. If investors believe the Fed will rescue them from their excesses, people will take greater risks and, ultimately, suffer greater consequences. Some grumble that the Fed created problems this way in 1998, 1999 and 2003.

If the Fed were to cut rates now, it certainly could help with the current market crisis. The cheaper money would reduce pressure on stock and bond markets by making it easier to buy beaten-down stocks, bonds and other securities world-wide. Wall Street is a powerful lobby in Washington, and its bleating for help can be hard to resist for politicians, whose campaigns often depend on financial contributions from Wall Street figures.

But if the Fed were to ride to the rescue, the skeptics worry, it would encourage people to speculate even more, creating an even bigger bubble later.

"You don't want to see the Fed bail out these guys who have made a lot of money. They have made their bed and you want to see them lie in it," says a veteran trader at a New York brokerage house. "Then again, you don't want to see the economy go into recession."

But Bernanke may be different. The Fed's policy announcements for the last 6 months have consistently stated the following:

......the Committee's predominant policy concern remains the risk that inflation will fail to moderate as expected. Future policy adjustments will depend on the outlook for both inflation and economic growth, as implied by incoming information.

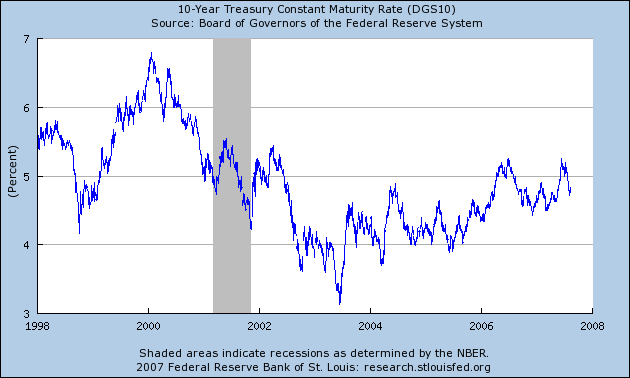

The Fed has consistently said it's primary policy goal right now is price stability. That means keeping rates where they are. I should also add that interest rates aren't that high right now. Here's a 10-year chart of the 10-year Treasury. Rates were a lot higher at the end of the 1990s when the economy was expanding faster than it is now.

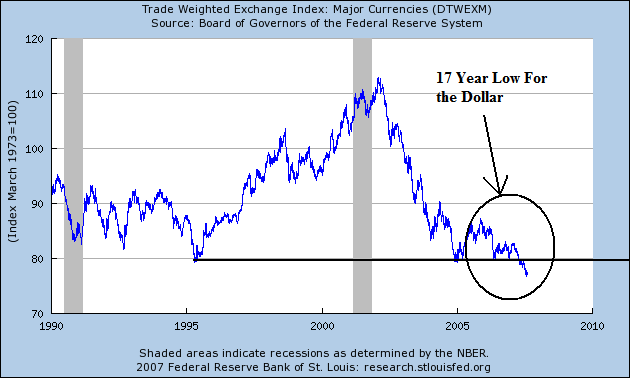

In addition, those arguing for a rate cut are ignoring this long-term chart of the dollar:

While I am just as guilty of making fun of Bernanke as the next guy, I honestly don't think Bernanke is going to lower rates barring a major catastrophe. Interventions? Yes; that's the Fed's job. But rate cuts? Not unless the crisis gets a whole lot worse.