- by New Deal democrat

This is Ben Casellman, Chief Economic Correspondent for The NY Times’s take on last Friday’s employment report:

I beg to differ. As I wrote Friday, underneath the headlines, this was a barely positive report - with some significant negatives. Let me point out a couple of the big ones today.

The headline was 147,000 jobs added, about average for the past year:

So it’s all good, right?

Not so fast.

That 147,000 breaks down to 74,000 private jobs + 63,000 education (and 10,000 other). In the past six years, only 3 other times have public sector jobs (including education and all other government jobs) been such a large component of the total gain:

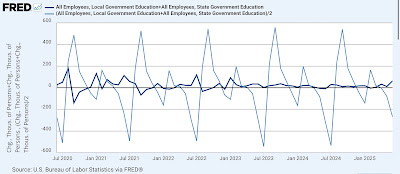

And the simple reason is that education employment is highly seasonal, with layoffs in May through July, and rehiring in August through October, as shown in the below graph where the non-seasonally adjusted numbers are in light blue, the seasonally adjusted ones in dark blue - and even then, I’ve had to divide the NSA numbers by 2 just to avoid the SA numbers being reduced to squiggles:

In June, “only” 271,000 education jobs were lost, which translated to a 63,000 SA gain. As one of Casselman’s correspondents pointed out, that may have to do with the fact that June started on a Sunday, so the reference week for the payrolls report was particularly early, and many school districts may not have ended their school year yet. In any event, regardless of the reason, that 63,000 gain is almost certainly going to be “paid back” next month.

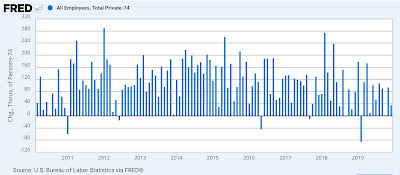

So how bad really is a 74,000 private sector gain?

In the entire decade-long expansion before COVID, there were only 5 times that private sector jobs had fewer than 74,000 gains:

And there have only been 6 such times since the pandemic:

Now let’s zoom out a little bit. In the first 6 months of this year, 644,000 new private sector jobs have been created, plus 138,000 government jobs. Here’s how that compares with the entire 40 year history before COVID:

And here is how it compares post-pandemic:

In the entire 45 year period, *not once* has there been such anemic private sector growth in one half of the year except for during, just after, and the half year just before recessions.

Further, as shown above, private sector job growth tends to be slightly leading. That’s basically simple arithmetic, because total employment is a classic coincident indicator, while government employment lags. That’s because government entities generally have to balance their budgets, and for the first 3 to 12 months of a recession, they base hiring on the prior year’s tax receipts. Since during a recession, those receipts go down, governments have to make cuts that last up to several years after the recession is over.

Here’s the historical view of just public sector employment (the same as in the above) in two graphs:

And here is the post-pandemic view:

In each case government job losses continued for up to two years after the end of the recessions, and sometimes continued to increase during the early parts of the recession themselves. In other words, the early losses were concentrated in the private sector.

Put another way, when private sector employment gains wane, that is a warning signal. And private sector gains have waned so far this year.

I think that’s a little more than squint-worthy.

Before I finish, let me update another important graph. Below is nominal aggregate nonsupervisory payroll growth (red) compared with CPI (orange), together with real aggregate nonsupervisory payrolls (blue) through May (since we don’t have June’s CPI number yet), all normed to 100 as of March:

Nominally, aggregate nonsupervisory payrolls have only risen 0.3% since March, while consumer prices have risen that same percentage just through May. In other words, real aggregate payrolls look like they have been peaking this spring. And as I have pointed out many times in the past, a peak in real aggregate nonsupervisory payrolls has been an excellent metric for forecasting a downturn in real consumer spending, and with it, a recession.

So, far from being healthy or “resilient,” as Casselman contends, the June employment report had a number of important danger signals, only the most important of which I have detailed here.