- by New Deal democrat

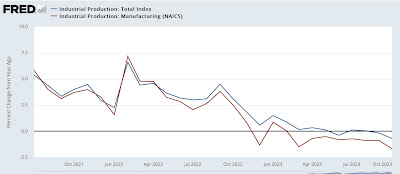

Yesterday I wrote of how manufacturing has faded somewhat as a leading indicator, at least in the sense that it takes a steeper downturn than it used to in order to forecast a wider downturn in the economy.

Which makes the other big goods-producing sector, construction, even more important. And residential housing is the single most component of that.

And even further, because of supply-chain issues during the pandemic, housing units under construction has been the most important metric of all, because they represent the actual economic activity of construction. As I wrote two months ago:

“total housing units under construction, although the most lagging of housing construction statistics, have also had to turn down before recessions begin. … multi-family units under construction, which typically turn after single family units, have also usually (except for 2008 and the pandemic) turned down before recessions have begun.”

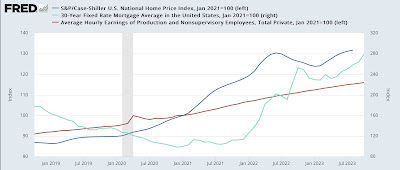

This morning’s residential construction report for October confirmed that the peak is most likely behind us - but on the other hand, the level still continues to levitate close to that peak. Total units under construction about 1% for the month, but are only -2.2% below their all-time peak exactly one year ago:

Single family units under construction also declined a little under 1%, and are -19.5% below their May 2022 peak, while multi-family units rose by just 1,000, and are only -0.4% down from their all-time peak three months ago:

This is simply not recessionary at all. It bespeaks continued if decelerating expansion.

Now let’s turn to the proverbial tip of the spear, permits (blue, right scale in the graph below). These rose 1.1% for the month, and have rebounded about 20% back from their recent lows in January towards their previous pea. Single family permits, which are the most leading and least noisy of all the metrics (red, left scale) also rose about 0.5%, and have retraced about 25% of their decline. Multi-family permits (gold, left scale) rose about 2% off their post-pandemic low least month:

Starts are much noisier than permits, and generally lag by one or two months. Total starts (blue, right scale) also rose this month and probably bottomed in August. Single family starts (red, left scale) rose slightly for the month and remain well off their lows from the beginning of this year, while multi-family starts (gold, left scale) like multi-family permits are just off their lows set several months ago:

In summary, there was no big change this month. Very elevated interest rates have continued to suppress the new housing market, which has caused buyers to turn to apartments and condos, while builders are finding ways to cut costs. All of the activity has peaked, including the most lagging component of multi-unit dwellings under construction, but total activity has barely declined off peak, meaning this most important leading sector of the economy continues to support relatively subdued expansion.