- by New Deal democrat

With no big economic news today, I thought I would pick up where I left off Friday, when I identified three major reasons for the economic tailwind that prevented a recession from happening in the past 12 months.

1. Commodity prices generally and gas prices specifically

I am beginning to think that all economic forecasts should come with an open caveat on the order of “subject to the trend in gas prices, which are set by a few geopolitical actors.” Certainly that was the case in 2022, when the War in Ukraine drove prices skyward, and then they fell back to ground as Europe in particular dealt with their reliance on Russian fuel.

This year prices rose as the economy strengthened, but they have fallen again in the past month, and averaged $3.50/gallon when I pulled this graph this morning, which is about -8% lower than 1 year ago:

Historically gas prices have a complex relationship with the economy. As shown in the graph below, gas prices averaged quarterly have a broad positive correlation with real GDP for the same quarter:

Which is another way of saying that large moves in gas prices affect the economy almost immediately (as in, “the remedy for high prices, is high prices.”)

But note the exceptions of 2006 and 2016. In both cases gas prices retreated sharply, even as an expansion continued (first due to the ebbing effects of Katrina, the second due to the success of fracking production in the US). A similar situation appears to be playing out in the past 12 months, where a big YoY decline in gas prices has been driving a sharp increase in GDP (which is expected to continue in the Q3 report this Thursday).

I also track industrial metals, which exclude the direct inclusion of energy prices. These also declined sharply this year. They appeared to be stabilizing, but in the past month have declined to new 12 month lows:

This may be traders’ reaction to the Israel/Gaza situation. But it may also have to do with continued weakness in China. So the commodity tailwind may be starting up again.

2. The slowdown in China

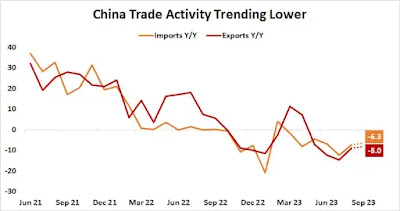

Below is a graph of imports to and exports from China measured YoY:

While I take all statistics about China with multiple grains of salt, if I saw this chart coming out of any transparent economy, I would treat it as recessionary. And because China is such a huge consumer of raw materials, I would treat it as placing further deflationary pressure on commodities, which we may be seeing with industrial metals in the past few weeks in the graph above.

3. Pandemic disruptions in the supply chains for houses and motor vehicles

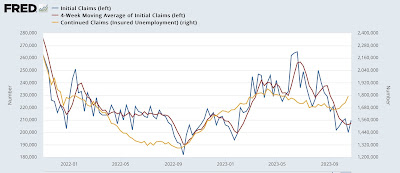

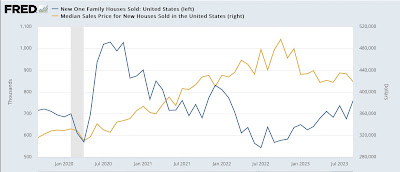

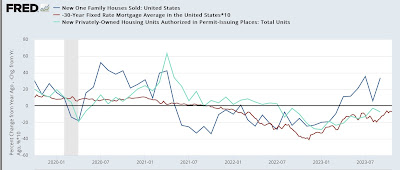

As I have noted many times, mortgage interest rates lead sales. With mortgage rates having hit 8% last week, let’s update the YoY graph of rates (inverted,*10 for scale) vs. housing permits:

One year ago mortgage rates hit 7%. But then they declined to 6% in the spring before rising to new highs more recently. So we cannot project current rates forward. But *IF* this uptrend in rates does not promptly reverse, then it is likely that permits will decline to new cycle lows below 1.350 million annualized, shown in the below graph of absolute mortgage interest rates and permits:

In fact, with interest rates about 10% higher (7%*1.10) than they were last year, a decline during winter to 10% below 1.350 million, or about 1.225 million, is possible.

And sooner or later, the big downturn in permits and starts is going to catch up with housing units under construction, which as I noted Friday are only down 2% so far.

The situation is much less clear when it comes to motor vehicles.

“S&P Global Mobility estimates that in 2021 more than 9.5 million units of global light-vehicle production was lost as a direct result of a lack of necessary semiconductors, with the third quarter of 2021 experiencing the largest impact with an estimated volume loss of 3.5 million units. Another 3 million units were impacted in 2022.

“During the first half of 2023, however, losses identifiable as specifically related to the semiconductor shortage fell to about 524,000 units globally.”

They also supply the following graph comparing backlogs in chip shipments compared with normal (normal=1):

At that time, the backlog was still about 3X the usual pre-pandemic time.

“Car manufacturers are struggling to keep up with the demand for new vehicles, as the shortage of chips has resulted in a shortage of critical components needed for production. It has also led to higher car prices as manufacturers pass on the additional costs to consumers.”

“Overall, the auto industry stocked 60 days’ worth of vehicles at the beginning of October. That’s considered a normal supply of inventory by historical standards, and it’s also the highest since early spring 2021”

But needless to say, it varies considerably with the popularity (or lack thereof) of the vehicles being sold:

“

brands like Dodge, Chrysler, Lincoln, Infiniti, Volvo, Ram, Jeep, and Mini offer plenty of new vehicle stock. In contrast, inventory levels still sit well under normal for Honda, Toyota, Kia, Subaru, Lexus, Cadillac, Land Rover, and Hyundai.”

To summarize the situation with motor vehicles, the chip shortage itself may be mainly over, but there is roughly 10,000,000 vehicles worth of pent-up demand that is far from being addressed. The net result for now is that vehicle prices have reached a new, stratospheric equilibrium, that is also constraining sales from satisfying that pent-up demand.