- by New Deal democrat

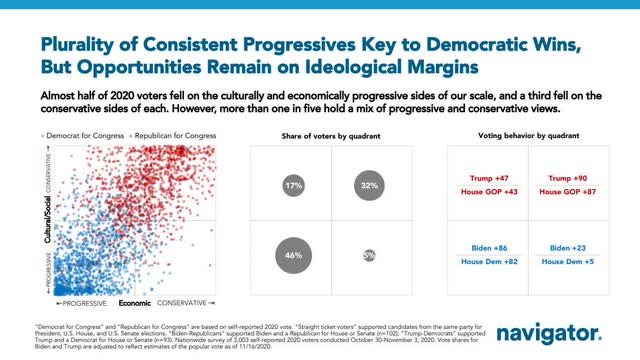

A few weekends ago I wrote that “the Democratic ‘brand’ is ‘socially liberal, economically moderate,’ while the US electorate as a whole is socially moderate and economically progressive” citing a scatterplot graph of the 2016 electorate; and that:

The path forward is to embrace, and pass, some simple economic fixes ... that materially improve - and are *seen* to materially improve - average Americans’ lives, while allowing for some flexibility on issues that people perceive as ones of morality (and hence are hard to compromise about) in such a way that nobody’s ox gets gored too much.

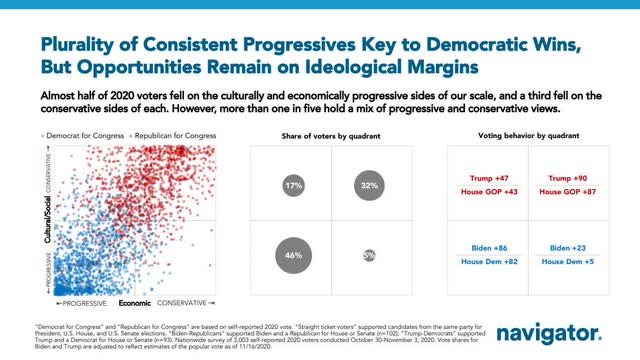

This past week that scatterplot diagram was updated and improved for the 2020 electorate. Here it is:

Biden got about 93% of the economically and culturally progressive vote. (Democratic congressional candidates got 91%.)

While Biden and Democratic congressional candidates did relatively well with the “libertarian” vote (socially liberal but economically conservative), they did poorly with the “populist” vote (economically progressive but socially conservative).

The problem for Democrats is that the “populist” vote is more than 3x as large as the “libertarian” vote. If Democrats were to trade their vote shares between those two groups (I.e., if conservatively Biden were to get 23% more of the populist vote, and lose the libertarian vote by 47%), here’s how the math would work out:

Of *total* votes, Biden would give up 3.1% from the libertarians and 4.7% of the populists, for a total of -7.8%, in exchange for 1.9% from the libertarians and 10.5% from the populists, for a total of +12.4%.

In short, Biden’s net vote gain would be 4.6%. Using similar math, Democratic Congressional candidates’ shares would improve by 2.9%, 10.3% of the total vote vs. 7.4% presently.

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that doing this trade would be tremendously advantageous to Democrats.

The upside is that Democrats could enact a thoroughly progressive economic agenda. But it’s certainly fair to ask, what the downside would be.

Start with the idea that “social issues” in most cases really are seen as “moral issues” by most people, and that’s why it is so difficult to find a compromise on them.

For example, 38 States allow 17 year olds to get married; of those 27 allow 16 year olds to be married. In 9 of those States a person over 21 years old can marry a person age 17 or even 16.

Suppose one of those married couples - say a man aged 24 and a teenage girl age 16 - moved into your State. Into your neighborhood.

Under the “full faith and credit” clause of the US Constitution, your State would have to recognize that marriage. It is a very open question to say the least whether your State’s laws criminalizing sex between those two persons could be enforced.

How does that “social issue” look to you?

Suppose you are the proverbial baker, who is a proprietor of your own business. If that couple wanted you to bake a cake for their first anniversary, do you think you should be able to lawfully refuse?

How does that “social issue” look to you?

The point I am trying to make in the above hypothetical situation is that the situation looks very different when it is *your* moral code that is being infringed upon.

To take another issue of recent contention, if I recall correctly even a majority of Democrats were against the forced removal of Confederate statues from all locations.

So, what would a “socially moderate” platform look like? It would probably entail two parts:

1. Allowing different States to make different moral choices within reason, even when it means some people who choose to live in some morally conservative States don’t have all the freedom you think they should have.

2. Allowing freedom of conscience for solo proprietors and family owned small businesses that do not take advantage of the corporate form to deny service to some customers to whom they have a moral aversion (but *not* on the basis of race).

The bottom line is, not forcing one portion of society’s version of morality down the craw of another portion of society, allowing breathing space, but ensuring that reasonable accommodations are made. As I said in my first post several weeks ago, ensuring that “nobody’s ox gets gored too much.”