Saturday, December 21, 2019

Weekly Indicators for December 16 - 20 at Seeking Alpha

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators post is Up at Seeking Alpha.

Are we just having a slowdown, or actually slipping into contraction? The short leading indicators would like to have a word.

As usual, clicking over and reading should bring you up to the moment on the economy, and rewards me a little bit for my efforts.

Friday, December 20, 2019

The consumer vs. producer divergence widens at year end

- by New Deal democrat

My economic theme for about the past half year has been the contrast between the floundering producer sector vs. the decent consumer sector. With two of the last important reports of the year out this morning, that divergence has been highlighted.

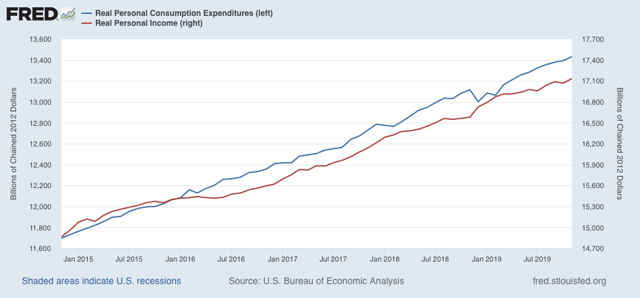

First, the good news: real personal income rose +0.4% in November, and real personal spending rose +0.3%. Here’s a look at the past five years:

No perceptible slowdown here!

But now, let’s look at the producer side, where the Kansas City Manufacturing Survey was the last of three regional surveys to be reported this week. Here is the moving monthly average of all five regions that I update in my weekly post:

Regional Fed New Orders Indexes

(*indicates report this week)

- *Empire State down -2.9 to +2.6

- *Philly up +1 to +9.4

- Richmond down -10 to -3

- *Kansas City down -13 to -16

- Dallas up +1.2 to -3.0

- Month-over-month rolling average: down -3 to -2

Today marks the very first time all year that the average of all five actually crossed into negative territory. This does not bode well for the December ISM manufacturing survey in particular, and for the manufacturing sector going forward into 2020 in general.

To conclude 2019: the consumer is alright. The producer, not so much.

Thursday, December 19, 2019

Political leanings through time for birth cohorts

- by New Deal democrat

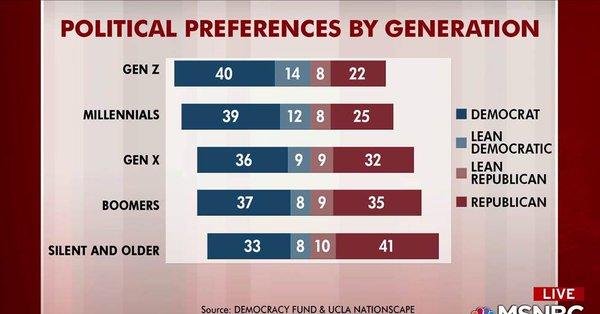

A chart on “political preferences by generation” from Pew Research has been making the rounds in the past few days. Here it is:

This chart tells the simplistic story that older generations are more conservative than young ones. It’s considerably misleading.

This chart tells the simplistic story that older generations are more conservative than young ones. It’s considerably misleading.

After all, how did the democrats ever win if older generations, who vote in higher percentages, are always more conservative than younger ones? The answer is, it’s not true.

Although Pew’s chart does not show the now-passed “greatest generation,” the simple fact is, that generations which came of age during the Great Depression and World War 2, and revered FDR, voted Democratic their whole lives.

As I’ve posted before, better way of looking at political preferences is to consider who was President during their teenage years. Because people tend to form their basic ideologies in their later teenage, or college years, and stick to it for the rest of their lives.

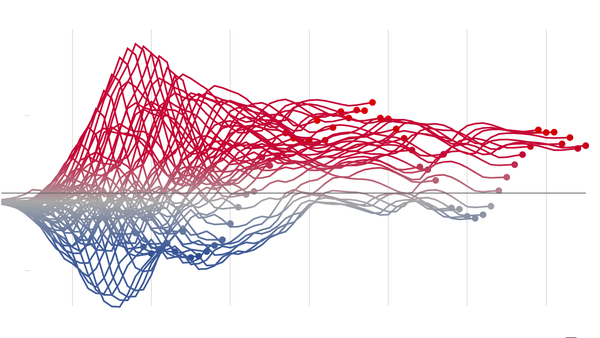

That is shown by this striking graph, of the evolution of political ideology over time for each birth year, from The Upshot today. The large circles show the ages and voting preferences for each year’s birth cohort as of the last election:

All of a sudden, that inexorable conservative drift with age disappears. Rather, people born during the LBJ and Nixon presidencies shifted ever bluer compared with those born before. Those who formed their ideologies during the unpopular Carter presidency, or during the Reagan years - basically, late Boomers and at the first half of Gen X - became the most conservative of all.

Over the next decade, as the oldest cohort dies off and the blue cohorts who formed their ideologies during the Clinton years and later vote in higher percentages, we can expect the electorate to turn more Democratic. But then, when the blue mid-Boomer contingent passes from the scene, over the next 15-20 years, the most conservative cohort of all, who have always worshipped at the altar of St. Ronnie, will also become the highest voting contingent of all.

A yellow flag for initial jobless claims

- by New Deal democrat

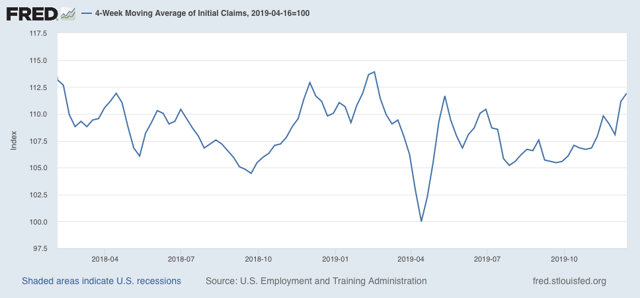

As you know, I’ve been monitoring initial jobless claims closely for the past several months, to see if there are any signs of a slowdown turning into something worse. Simply put, if businesses aren’t laying employees off, those same people are consumers who are going to continue to spend, which is 70% of the total economy. So the lack of any such increase has been the best argument that no recession is imminent.

This morning’s report of 234,000 initial claims is enough to put us over the threshold to a “yellow flag,” but historically still has more often coincided with slowdowns rather than recessions.

To reiterate, my two thresholds for initial claims are:

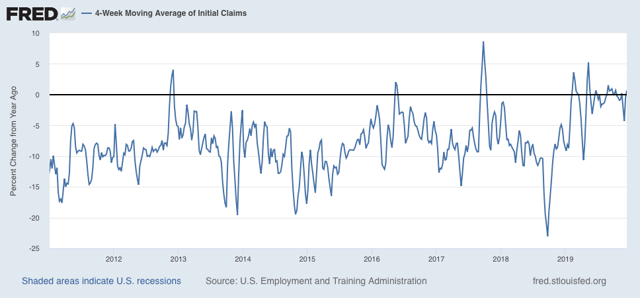

1. If the four week average on claims is more than 10% above its expansion low.

2. If the YoY% change in the monthly average turns higher.

Aside from last week’s 252,000 claims, this week was the weakest but for two weeks since January of 2018. As a result, the 4 week moving average of claims has risen to 225,500, and is 11.9% above the lowest reading of this expansion, which occurred back in April:

On a YoY% change basis, the 4 week average is 1,500, or 0.7%, higher:

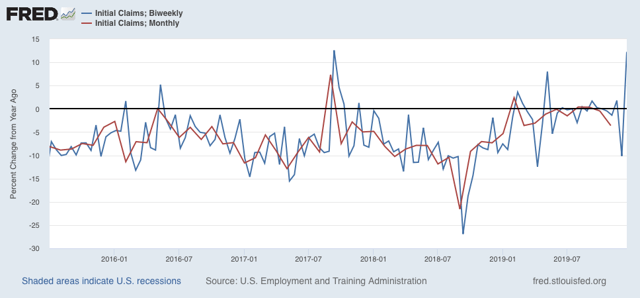

For the first two weeks of December (blue in the graph below), the average is 243,000 vs. 223,200 for the entire month of December last year (red), or higher by 9.0%, while on direct comparison with the first two weeks of last December, they are higher by 12.2%:

In short, pending the completion of December for a direct month to month comparison, both thresholds for initial claims have been met this week.

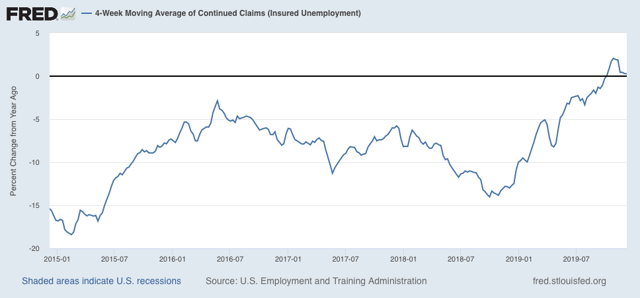

Meanwhile, the less volatile 4 week average of continuing claims is 0.3% above where it was a year ago:

Here is the longer term graph:

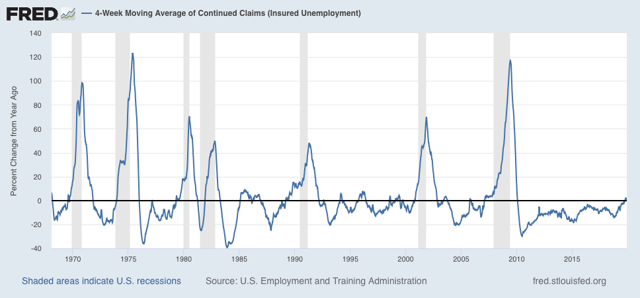

The four week average of continuing claims, while cautionary, is consistent with a significant slowdown. But there have been similar readings in 1967, 1985-6, 3 times in the 1990s, and briefly in 2003 and 2005, all without a recession following. So the threshold for continuing claims being a negative (vs. neutral) has not been met.

Several weeks ago I wrote that “unless initial claims start to be reported in the 230’s, and continuing claims continue to trend higher, into the 1.770 million range (by mid-December, after which the YoY comparisons for continuing claims get much easier), no interim recession will be signaled.”

For the last two weeks, both numbers have been in the 230’s or higher, and 4 of the last 6 weeks have been above 225,000. Because continuing claims have not climbed meaningfully higher, and because we still have two weeks left in December, there is no red flag.

For the record, if the four week average of claims is more than 12.5% higher than their low, that will be a red flag. If they move more than 15% higher, and the YoY changes are higher for two months in a row, that would mean a near-term recession were almost certain.

For the last two weeks, both numbers have been in the 230’s or higher, and 4 of the last 6 weeks have been above 225,000. Because continuing claims have not climbed meaningfully higher, and because we still have two weeks left in December, there is no red flag.

For the record, if the four week average of claims is more than 12.5% higher than their low, that will be a red flag. If they move more than 15% higher, and the YoY changes are higher for two months in a row, that would mean a near-term recession were almost certain.

But we have just enough as of this week to move this short leading indicator to a yellow flag, I.e., from neutral to weakly negative.

Wednesday, December 18, 2019

October JOLTS report shows soft patch in employment

- by New Deal democrat

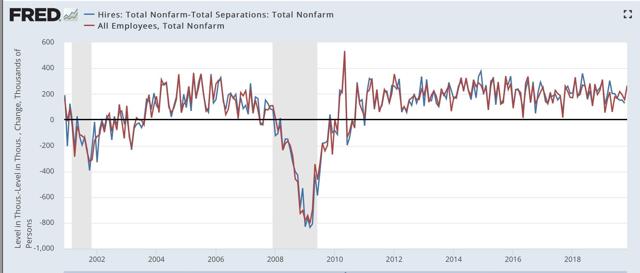

Let’s take a look at yesterday morning’s JOLTS report for October. I thought I’d start off this month by stepping back and comparing the monthly change in employment from the jobs report (red) with the monthly total of hires minus total separations from the JOLTS report (blue), going all the way back to the beginning of the latter series in 2001:

Note that the monthly changes are almost always very close.

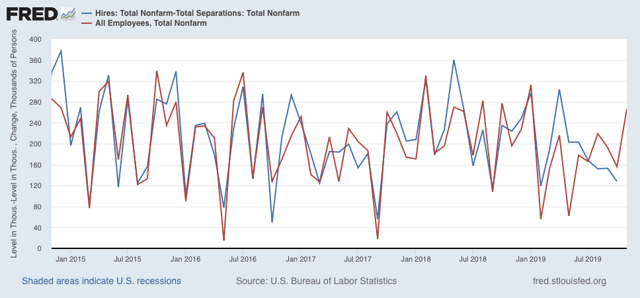

Here is a close-up of the past few years:

By contrast, since April of this year the series have diverged significantly. I’m not sure what the reason is, but it is something to keep an eye on.

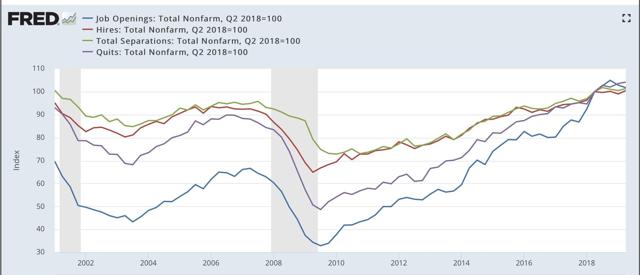

Next, let’s review the order in which the JOLTS series peaked during the 2000s expansion:

- Hires peaked first, from December 2004 through September 2005

- Quits peaked next, in September 2005

- Layoffs and Discharges peaked next, from October 2005 through September 2006

- Openings peaked last, in April 2007

as shown in the below graph (quarterly, normed to 100 as of May 2018):

Here is the close-up on the past few years (monthly), normed to 100 as of August 2018:

In the past 14 months, with the exception of job openings, these series have essentially gone sideways, with job openings and hires both below their levels then, and quits and separations only slightly (1.1% and 0.6%) higher, respectively.

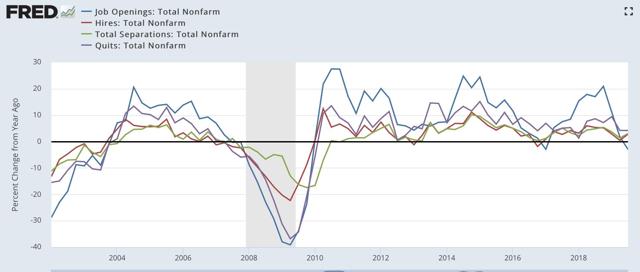

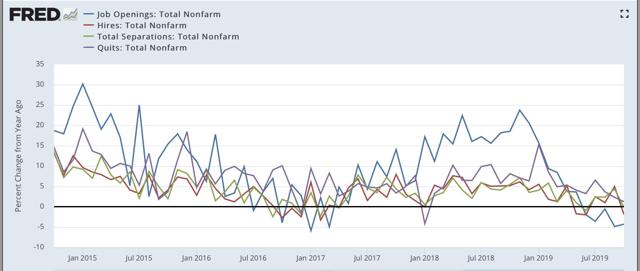

Here is the same data tracked YoY, first quarterly since 2001:

Note that hires and total separations turned negative YoY first, in Q1 2007, followed by quotes and openings in Q3.

And now focused on the past five years:

The soft patch during the shallow industrial recession of 2015-16 is evident. The current soft patch is not quite so negative.

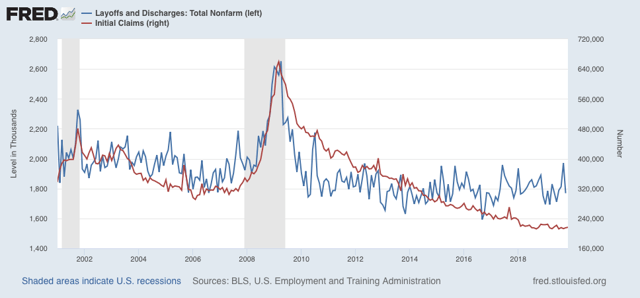

Finally, For completeness’ sake, below are total layoffs and discharges (blue). Note that these turned up appreciably in the six months or so before the Great Recession. This month I thought I would compare them with initial jobless claims (averaged monthly, red) to compare which gives better signals of turning points:

As you can see, both peaked at the same time near the end of the last two recessions, but initial claims are much less noisy in the lead-up to recessions, and so are the better indicator.

Because November’s jobs report was so strong, I am expecting a better JOLTS report next month. In the meantime, the soft patch in the employment market is evident.

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Live-blogging the Fifteenth Amendment: December 17, 1868

- by New Deal democrat

In the Senate, Senators Dixon and Ferry, both Republicans from Connecticut, continued the debate from several days prior concerning a federal imposition of African-American voting rights on the States:

Dixon:

[M]y colleague ... proposes to amend the Constitution of the United States in a manner which to me is very revolting, not because I hate negro suffrage, but, sir, I do desire that the proud old State of Connecticut, shall not be humbled in the dust. Having enjoyed the right of suffrage and of regulating her own right of suffrage for over two hundred years — longer, I believe, than any State in the Union — I do not desire that at this late day she should be compelled to submit to the demands ... of any other State with regard to who shall vote within her borders . . . .

Ferry:

With regard to an amendment to the Constitution of the United States removing the distinctions of color now existing in different States of the Republic I had certainly hoped that my colleague would be willing to stand side by side with me in the support of it. I know that he had twice in my State voted with me for a constitutional amendment there to extend the franchise to the negro; and I ask what difference is there between an amendment to the constitution of my State and an amendment to the Constitution of the United States for the purpose of accomplishing the same object? . . . .

Dixon:

I prefer leaving it to the State of Connecticut to decide for herself; and that was the substance of Dr. Bacon’s letter. He said he was in favor of negro suffrage, but preferred that the negroes should never vote rather than that negro suffrage should be forced upon Connecticut by act of Congress; and you may say the same thing of an amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

[ Source: Congressional Globe, 40th Congress, 3rd Session, pp. 123-124, Appendix, p. 50 ]

The above exchange highlights what Dr. Foner refers to in his book “The Second Founding.” For the proponents of the Fifteenth Amendment were proposing that the Federal government be given the right to demand and enforce voting rights in the States, which was anathema not only to most Jacksonian Democrats, but also to some anti-slavery Republicans as well.

————

December 7, 1868

————

Previous installments:

November housing and production both up sharply

- by New Deal democrat

We got two of our final most important reports of 2019 this morning. Both were positive, one strongly so.

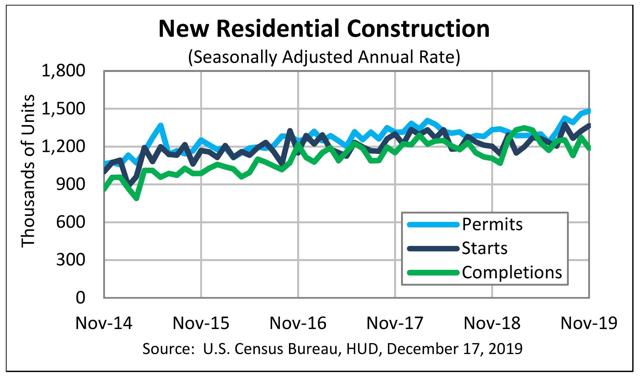

Starting with the best and most forward-looking news, housing permits and starts both improved strongly in November:

I’ll have a more detailed report up at Seeking Alpha later today, and I’ll link to it here once it’s up. The bottom line is that lower interest rates have re-ignited the housing market, and that good news is going to flow through the economy in 2020. [UPDATE: Seeking Alpha article is up here ]

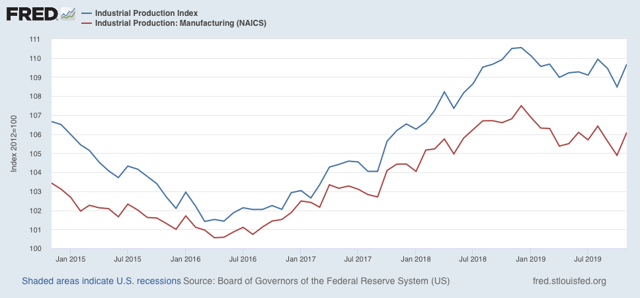

Industrial production, the King of coincident indicators, was also up a sharp +1.1% in November (blue in the graph below). Most of that was the end of the GM strike, but even without that, production was up +0.6%:

One important drawback in this number, though, is that manufacturing production, while up for the month, is still lagging (red in the graph above) and if anything, appears to still be in a slight downtrend.

All in all, this tells us that right now we are in a shallow manufacturing recession, but that the situation in the economy overall should improve as we head out of winter towards summer next year.

Monday, December 16, 2019

The oncoming generational UK and US political tsunamis

- by New Deal democrat

No big economic news today, so let me put up a couple of striking charts about the UK election last week.

First, the change in party results in 2019 (left) vs. 2017 (right) in millions:

Tories: 13.9. 13.6

Labour: 10.3. 12.9 (a 20% decline!)

Lib Dems: 3.7 2.4

SNP: 1.2 1.0

Total turnout was down 1.5%. As should be obvious, as the accompanying commentary said, the Tories didn’t win; Labour lost, and terribly. Apparently having a leader (Jeremy Corbyn) with a -44% approval rating, and no substantive position at all on the most important issue in decades, Brexit, was a loser. Hoocoodanode?!?

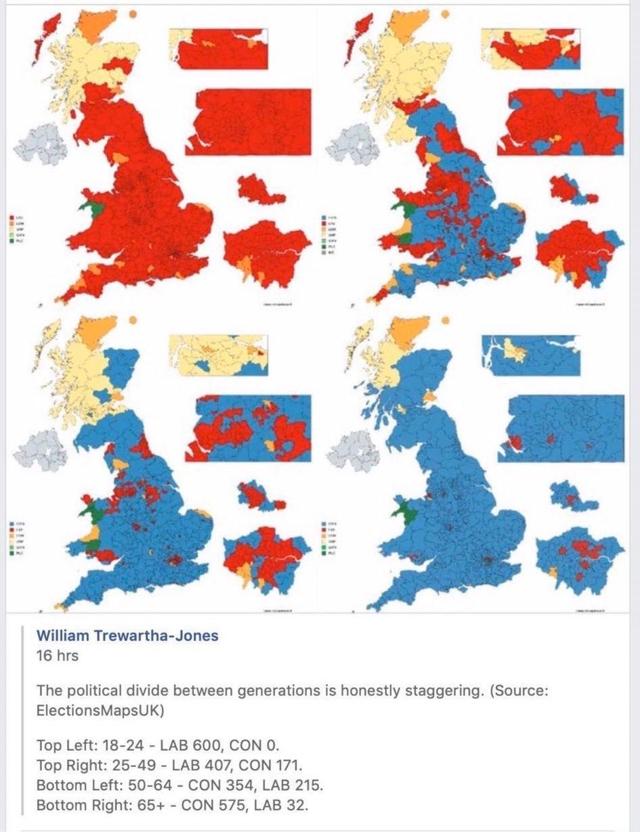

Second - and this is really stunning - which party won seats based on age group:

The conservatives won precisely *zero* seats among the youngest voters.

Meanwhile Labour won only 32 seats among the oldest.

More generally, there was a Labour landslide among voters under 50. But an even larger Conservative landslide among voters 50 and older. One caveat: I don’t know the source for this information, because voting is of course anonymous. Probably the information comes from exist polls, so take with a few grains of salt.

Since people tend to form their basic political ideologies in their later teens or early twenties, at some point - probably within the next 10 years - there is likely to be a political tsunami in the UK sweeping away right wing economic policies.

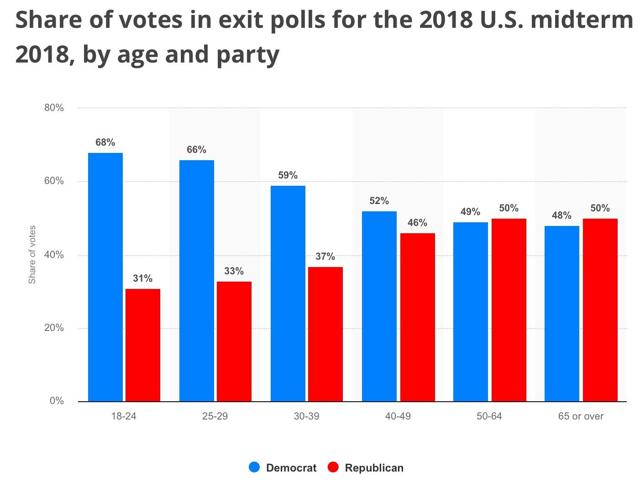

That made me go look for a similar breakdown of the 2018 US Congressional elections. The below graph is the closest thing I found:

Interesting that the inflection point seems to be at age 50 in the US as well. People who formed their political views in the Reagan era or earlier in the US, and the Thatcher era and earlier in the UK, skewed conservative, while those whose views were formed later skewed to the left.

In the UK, the immediate risk is that the union itself ruptures, with Scotland and possibly Northern Ireland as well leaving. In the US, the risk is a rupture of the Constitutional fabric, by way of heightened mutual “hardball” and political violence, and a significant chance of a slide into Presidential autocracy.

Sunday, December 15, 2019

Live-blogging the Fifteenth Amendment: December 15, 1868

- by New Deal democrat

Sen Orrin S. Ferry (R-Conn), in the course of offering a joint resolution to lift the disabilities mandated by the 3rd Section of the Fourteenth Amendment against those who participated in the rebellion:

[I]t does seem to me as if the experience of the last fifty years ought to enlighten us as to the chimerical character of the dangers which have been apprehended from the extension of suffrage and to eligibility to office at one time and another.

It has been thought once, even in this land, that poverty disqualified a man from voting, and no man, unless he was the owner of property, was permitted to exercise the suffrage. Time went on; the property qualification disappeared; and nowhere are the law and order more respected, are person and property more secure than in those communities where suffrage is most universal and government rests upon the broadest foundation.

It has been thought that dangers might assail us in the influx of the enormous immigration from the Old World, and a great party was once organized upon that very apprehension. The fear has passed away, for time and experience have demonstrated that the evils accompanying that immigration are but temporary, and will pass away in a single generation.

The time has been when the negro was a beast of burden, and nothing else. The time is now when good men too often apprehend the danger of the extension of the suffrage unto him be reason of the ignorance which is the result of centuries of slavery; but it is beginning to be seen by the practical operation of the laws extending suffrage [mandated by the Congress in the constitutions of reconstructed States], that all these fears are chimerical, and that the black man as well as the white is an element of strength and prosperity in civil society.

In support of the resolution, Sen. Willard Warner, a union general, who moved from Ohio to Alabama after the war, and was elected to the Senate from Alabama in 1868, argued that a Republican-controlled legislature in Alabama had removed the disabilities to those who had engaged in rebellion, but that even after that, Republican candidates had triumphed in the next election.

To which, Garrett Davis, a unionist KY Democrat, replied:

[S]uppose there was no military force moving from this center, this capital, and from States and places outside of Alabama, what would become of the honorable Senator’s negro government and of his representation of it in this body? I am inclined to think they would be fugitives from it.

.... I will never consent that the Congress of the United States shall vote to force negro suffrage upon the State of Alabama or the State of Kentucky or any other State; and I assert that Congress has not a vestige of power to enforce such a constituency upon the people of any State.

The honorable Senator [Warner] ... seems to be very much enamored with the idea of negro suffrage, and he seems to think that I and my political party are responsible for the non-existence of that political power in the other States. Who voted down negro suffrage in Kansas? Who voted down negro suffrage in Ohio? Who voted down negro suffrage in Michigan, but the honorable Senator’s political friends.... Now, when Ohio by more than forty thousand, Kansas by eight or ten thousand, Michigan by twenty or thirty thousand, all the northern States, where there are no negroes to vote, voted down the principle of negro suffrage by such immense majorities, with what grace can they or their southern auxiliary, the Senator from Alabama, vote to force negro suffrage upon the ten southern States, under the principle of the Constitution of the United States that the people of a State have the sole and exclusive power of framing their own governments.

As Davis pointed out, when it came to their own States, northern States had refused to grant to African-Americans the right to vote. That a majority of their own constituents did not actually believe in racial equality, but that the effects of the Fifteenth Amendment would overwhelmingly be felt in the South, has to be taken into account when considering why the Amendment wound up being more narrowly crafted.