Saturday, November 16, 2019

Weekly Indicators for November 11 - 15 at Seeking Alpha

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators post is up at Seeking Alpha.

Although a few indicators backed off some this week, the overall tone, ex-manufacturing, across all timeframes is positive.

You may be reading a few takes today about the poor nowcasts out of the NY and Atlanta Feds, after yesterday’s face-plant of an industrial production reading. Keep in mind that they are mechanically applying that result and not accounting for the GM strike (which is what I would do if I were in their shoes as well). So take those with a healthy dose of salt for now.

As usual, clicking over and reading rewards me with a couple of pennies for my efforts.

Friday, November 15, 2019

Industrial production tanks on GM strikes; Real retail sales decline slightly

- by New Deal democrat

First, let me briefly address industrial production, which fell -0.8% in October. On its face this is an awful number. But take it with a big grain of salt: mainly it reflected the GM strike.

Here’s the applicable note from the Federal Reserve:

Manufacturing output fell 0.6 percent in October to a level 1.5 percent lower than its year-earlier reading. In October, the strike in the motor vehicle industry contributed to a drop of 1.2 percent for durables. Excluding motor vehicles and parts, the output of durables moved down 0.2 percent.... The production of nondurables was unchanged.... The output of other manufacturing (publishing and logging) fell 1.0 percent.

Even without the GM strike, the number would have been negative. But not nearly as negative as it was. For the record, both utilities and mining (including oil production) were also down substantially, but these tend to be volatile.

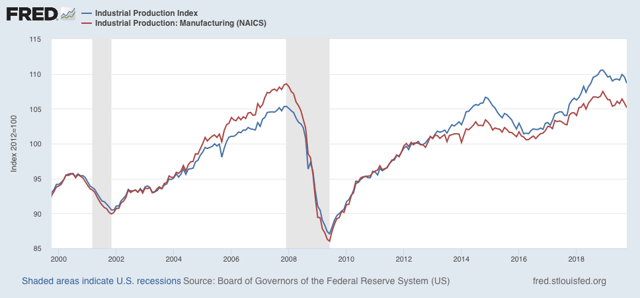

So here is the relevant graph, which certainly does show a downturn in the past year. Just take the last downward blip with a grain of salt:

Now let’s turn to retail sales. Retail sales are one of my favorite indicators, because in real terms they can tell us so much about the present, near term forecast, and longer term forecast for the economy.

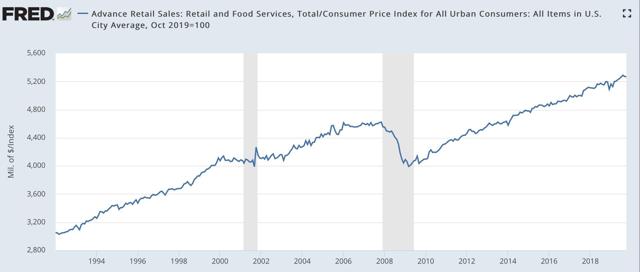

This morning retail sales for October were reported up +0.3%, taking back September’s -0.3% decline. Since consumer inflation increased by +0.4%, however, real retail sales declined -0.1% for the month, following another -0.1% decline in September. As a result, YoY real retail sales took a spill but are still up +1.3%.

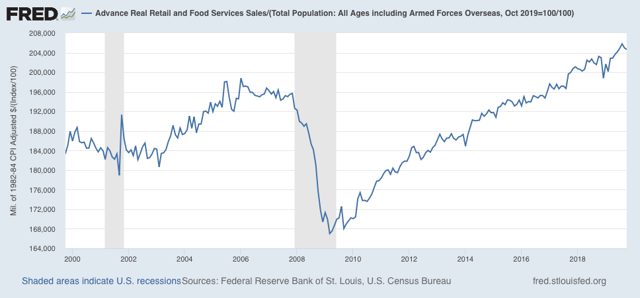

Here is what the absolute trend looks like. The last two months’ decline remains well within the range of noise:

Others may use other deflators. I use overall CPI because:

1. I’ve been doing it this way for over 10 years.

2. This is the deflator used by FRED.

3. It has a 70+ year history.

4. Over that 70+ year history, it has an excellent record as a short leading indicator for employment and recessions. That’s the kind of track record I like.

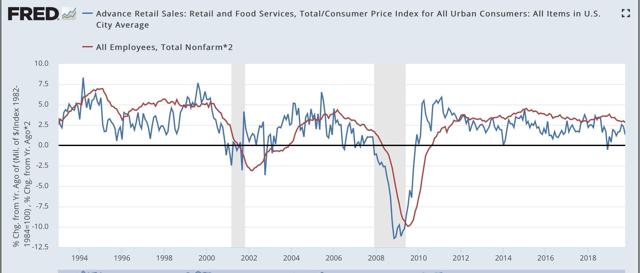

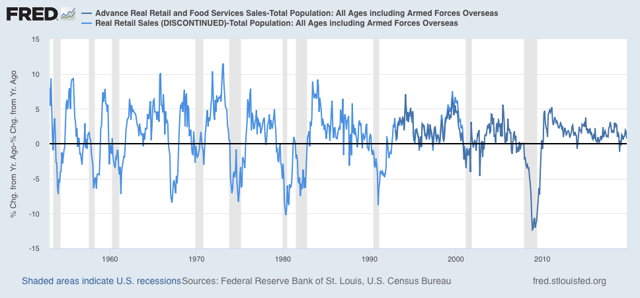

Further, although the relationship is noisy, real retail sales measured YoY tend to lead employment (red in the graphs below) by about 4 to 8 months. Here is that relationship over the past 20 years:

The recent peak in YoY employment gains followed the recent peak in real retail sales by roughly 6 months, and the downturn in real retail sales at the end of last year has already shown up in weakness in the employment numbers this year. Similarly even with the October decline I expect the recent improvement in retail sales YoY to show up in at least stabilization in the employment numbers by about next spring.

Finally, real retail sales per capita is a long leading indicator. In particular it has turned down a full year before either of the past two recessions:

In the last 70 years, with the exception of 1973 and 1981 this measure has always turned negative YoY at least shortly before a recession has begun:

Thus this is a quite reliable indicator.

In summary, while a two month decline in real retail sales is a negative, this is a small one. It will take a significant further decline for me to become concerned.

Thursday, November 14, 2019

Initial claims continue to show slowdown, but no imminent recession

- by New Deal democrat

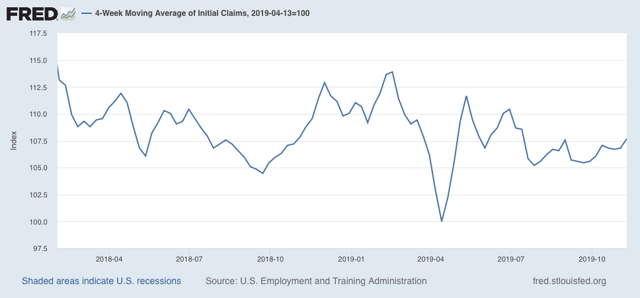

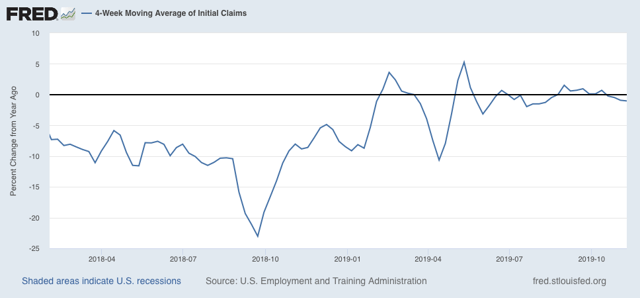

I’ve been monitoring initial jobless claims closely for the past several months, to see if there are any signs of a slowdown turning into something worse. Simply put, no recession is going to begin unless and until layoffs increase.

My two thresholds are:

1. If the four week average on claims is more than 10% above its expansion low.

2. If the YoY% change in the monthly average turns higher.

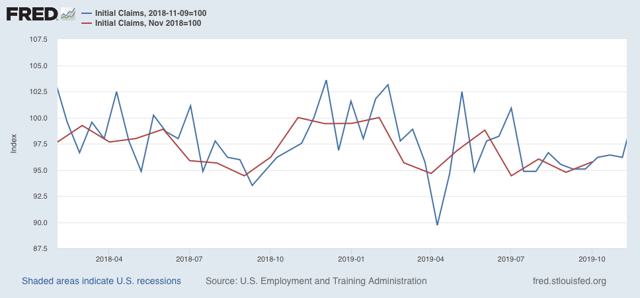

As of this week, initial claims continue to be very close to their expansion lows. The 4 week moving average of claims Is 217,000, only 7.7% above the lowest reading of this expansion:

On a YoY% change basis, the 4 week average is -1.0% below its level one year ago:

In the first two weeks of November(blue), the average is 218,500 vs. 224,500 for November last year (red):

Although these readings are all weak, they remain positive. Neither threshold for a cautionary recession signal has been met.

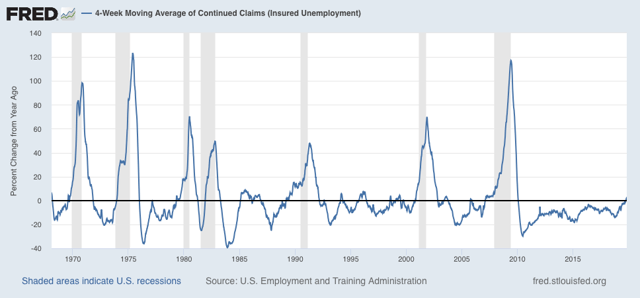

On the other hand, the less volatile (but less leading) 4 week average of continuing claims is 1.5% above where it was a year ago:

This certainly is cautionary, and is consistent with a significant slowdown. But there have been similar readings in 1967, 1985-6, 3 times in the 1990s, and briefly in 2003 and 2005, all without a recession following. If we were to get readings in this metric more than 5% higher YoY, then I would be concerned.

Bottom line: unless initial claims start to be reported in the 230’s, and continuing claims continue to trend higher, there isn’t a recession in the immediate future (and, based on the improvement in the long leading indicators this year, barring more poor government policies, if there is no recession by midyear next year at the latest, it’s not going to happen).

Wednesday, November 13, 2019

Real average and aggregate wages declined in October

- by New Deal democrat

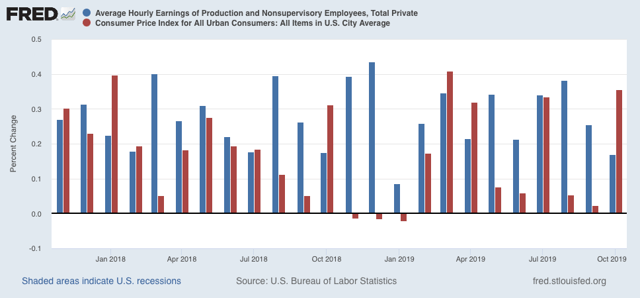

October’s consumer inflation reading came in at a surprisingly high +0.4%, which as shown in red in the graph below, was one of the 3 highest in the past two years. Meanwhile average hourly earnings increased less than +0.2% - the second lowest reading in the past two years, shown in blue:

As a result, real average hourly earnings decreased -0.2% last month, the worst reading since late 2017:

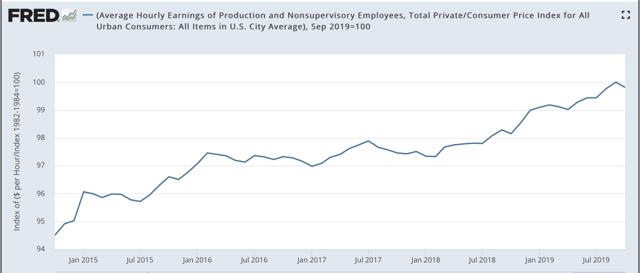

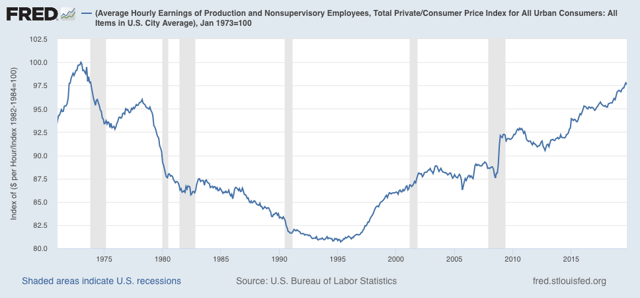

In a longer term perspective, this means that real wages declined to 97.6% of their all time high in January 1973:

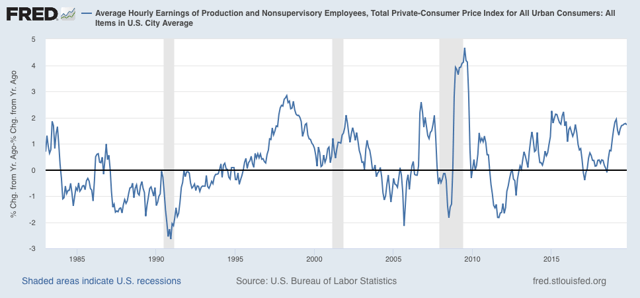

On a YoY basis, real average wages remained up +1.7%, as they have been since June, and still below their recent peak growth of 1.9% YoY in February:

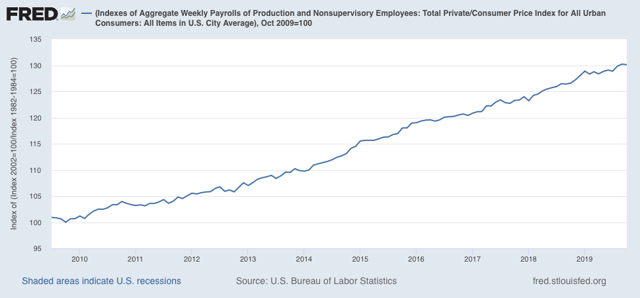

Aggregate hours and payrolls have improved significantly since July, so even though they declined -0.1% in October, real aggregate wages - the total amount of real pay taken home by the middle and working classes - are up 30.1% from their October 2009 trough at the beginning of this expansion:

For total wage growth, this expansion remains in third place, behind the 1960s and 1990s, among all post-World War 2 expansions; while the *pace* of wage growth has been the slowest except for the 2000s expansion.

Tuesday, November 12, 2019

How economists blew the analysis of the manufacturing jobs shock

- by New Deal democrat

I came across this article yesterday, posted by - to his credit - Brad DeLong, whose argument it eviscerates. Entitled “The Epic MIstake about Manufacturing That’s Cost Americans Millions of Jobs,” it deserves widespread attention. So I am summarizing it here. But by all means go and read the entire piece.

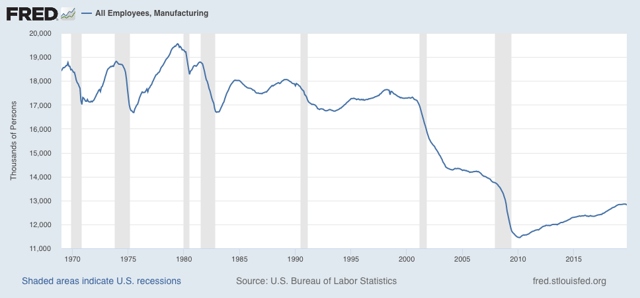

Just to give you the frame of reference, here is the historical graph of manufacturing jobs in the US for the past 50 years:

After peaking in 1979, the number more or less gradually declined in the 1980s, and then stabilized in the 1990s, before plummeting right after 2000.

As written by Gwynn Guilford, the consensus of economists’ opinion was that while

the US had hemorrhaged manufacturing jobs, losing close to 5 million of them since 2000. Trade may have been a factor—but it clearly wasn’t the main culprit. Automation was.

....

For a decade or so, this phenomenon had been put forth by Ivy League economists, former US secretaries of treasury, transportation, and labor, Congressional Research Services, vice president Joe Biden, president Barack Obama—and by Quartz too, for that matter. In a 2016 New York Times articletitled “The Long-Term Jobs Killer is Not China. It’s Automation,” Harvard economist Lawrence Katz laid out the general consensus: “Over the long haul, clearly automation’s been much more important—it’s not even close.”

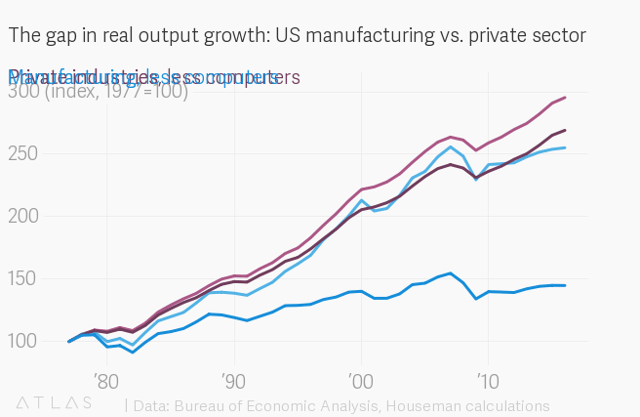

Susan Houseman, an economist at the Upjohn Institute, and her colleagues, examined microdata available from the Federal Reserve, and discovered that this entire rationalization was based on technological improvements in only one industry — computers. As the article states, once they

strip[ped] away the computers industry output from the rest of the data[, t]hat revealed just how the rest of manufacturing was doing—and it was much worse than what Houseman and her colleagues expected.

“It was staggering—it was actually staggering—how much that was contributing to growth in real [meaning, inflation-adjusted] manufacturing productivity and output,” says Houseman.

The culprit was “quality improvement.” The computing power of your smartphone is probably millions of times better than the Univac computer of the 1950s. In fact, it’s much better than its ancestor of only 10 years ago. So your new smartphone is clearly worth “more” than an equivalently priced smartphone of 10 years ago.

The problem is, this quality improvement was assumed to be general across all of American industry. It wasn’t. Strip away computer quality improvement, and, well:

according to Houseman’s data, without computers, manufacturing’s real output expanded at an average rate of only about 0.2% a year in the 2000s. By 2016, real manufacturing output, sans computers, was lower than it was in 2007.

Here’s the nut graph (if the formatting doesn’t show properly, the important thing to know is that the light blue line well below the others is real manufacturing output less computers):

To put this in more dinosaurian terms, imagine if American factories were churning out exactly as much of exactly the same stuff in 2019 as they had been in 1969. Obviously we would say that there was no growth at all. But now make one change: where in 1969 automakers were churning out 10 million 1969 Chevy Impalas, in 2019 they are churning out 10 million 2019 Honda Accords. OK, modern Accords are light-years better than the Impalas of long ago, but we wouldn’t say that American industry across the board had improved.

That’s the mistake that economists made. Take away improvements in the computer industry, and American manufacturing really hasn’t made any progress at all - and still there are 4.5 million fewer jobs in manufacturing than there were at the end of 1999. And all of those jobs outside of the computer industry were due not to automation, but to trade.

Since the 2016 election, I’ve been leery of choosing sides between the “economic anxiety” trope and the “they’re all racists” theory, because I don’t see them as necessarily inconsistent. A white racist who is content with how things are going might vote for, e.g., Barack Obama, while that same racist, if stressed, will look for a scapegoat - like Mexicans and Muslims - to blame. Obama himself in a “Kinsey gaffe” referred to people “who cling to their guns and their religion.” That’s why in 2016 the national election result tracked so well with the economic voting models, while among the hardest-hit places in the 2016 “shallow industrial recession” were those of the upper Midwest that put Trump over the top.

Monday, November 11, 2019

November leading reports point to slowdown, no recession

- by New Deal democrat

The leading indicators reported so far this month show that, while manufacturing continues flat or even in contraction, there’s no significant indication that it has spread to other important sectors like residential construction or motor vehicle sales. And without the weakness spreading to their sectors, this looks similar to 2016, where there was a slowdown but no recession.

This article was posted last week at Seeking Alpha. As usual, clicking over and reading rewards me with a penny or two for my efforts.