Saturday, March 23, 2019

Weekly Indicators for March 18 - 22 at Seeking Alpha

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators post is up at Seeking Alpha.

As you can imagine, the big news was about the fact that almost every single yield curve there is - except the one I report on every week in that post - inverted yesterday.

Also, as I mentioned in an e-mail to a couple of folks this morning, the big thing that bothers me is that ***EVERYONE*** is watching it. And a forecasting tool that everyone pays attention to, ceases to be an accurate forecasting tool. It’s called “Second Order Chaos.” Humans are very clever and intelligent chimpanzees, and when you observe them, they observe you back, and react to the observation.

Anyway, as usual, clicking over and reading helps reward me with a little $$$ for my efforts.

Friday, March 22, 2019

... And, the 10 year treasury yield inverts

- by New Deal democrat

Yesterday over at Seeking Alpha I wrote about how the Fed is boxed in. The essence of the article is that, while lower rates are good for the housing market, a fuller yield curve inversion adds to the evidence that a recession may take place first, unless the Fed completely reverses course and starts cutting interest rates very soon.

Please click on over and read the whole article. Not only should it be educational for you, but it rewards me a little for my efforts in writing about the economy.

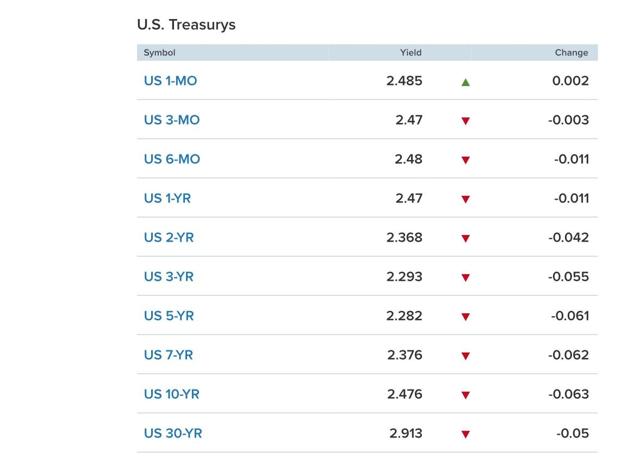

And so what do I see when I check out interest rates this morning? This:

For the first time, the yield curve inversion has spread to the 10 year Treasury, which is yielding less than either the 6 month or even the one month Treasury bill.

On December 3, the 2- and 3- to 5 year Treasury yield inverted, with the shorter maturities paying more than the longer maturity.

The next morning in a post entitled “The Camel’s Nose is in the Tent - Maybe,” which I’ll quote from at length below:

———-

Most of the commentary you have read probably boils down to an assertion that this is bad (it is) and that a recession is now likely in the next 12 to 24 months (maybe). ...

[Historically, w]hen the 2 to 5 year spread [has] inverted, typically the 2 to 10 year spread did so simultaneously or very shortly, as in days or a week, later. Usually later, so did the 10 to 30 year spread. In fact, when all three of those levels were in inversion simultaneously, a recession always followed within 12 to 24 months. But, even if we just consider the 2 to 5 year spread, its inversion usually was a prelude to a full spread inversion of the yield curve.

In other words, as the saying goes, "the camel's nose is in the tent." If you're not familiar with the saying, it means that the rest of the camel is likely to soon follow, with bad consequences for the people in the tent.

———-

I went on to note a few exceptions:

———

1. Several times - at the end of 1994 and the beginning of 1998 -- an inversion only happened for one day or even only intraday. [That did] not signal an oncoming recession ....

2. The 10 to 30 year spread had a number of false positives. We don't have to worry about that for now.

3. [T]he second half of 1998 a false positive as well, since no recession began until nearly 3 years after the inversion started, and over two years after it ended....

....

Most significantly, as in 1998, the Fed might react. If you are aware of the history of an inversion, and if I am aware of the history of an inversion, and if all of the other commentators who are writing about it are aware of the history of an inversion ... then don't you think the Fed and its economists might possibly discuss the possible implications of an inversion[?] ....The Fed is an actor. The Fed has agency. The Fed can affect the future course of the bond market. The Fed can react to this news if it chooses, and thereby change the future.

————

As I noted yesterday, the Fed did indirectly (via a steep stock market sell-off) respond to that inversion by changing its tone several weeks later, and earlier this week it pretty much eliminated the likelihood of any further rate hikes this year. But as I also noted, that might not be enough. The Fed may need to cut rates, and very soon, in order to stave off.a recession.

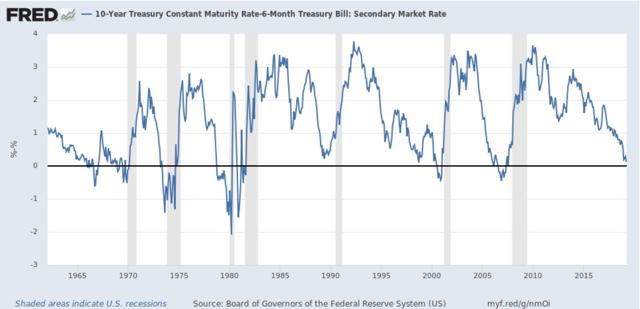

So let’s update through this morning. First, here’s what the 10 year minus 6 month treasury yield spread looks like for the past 60 years:

Aside from exactly one day in 1998, the only false positive was in 1966. Every other time this range inverted, a recession followed.

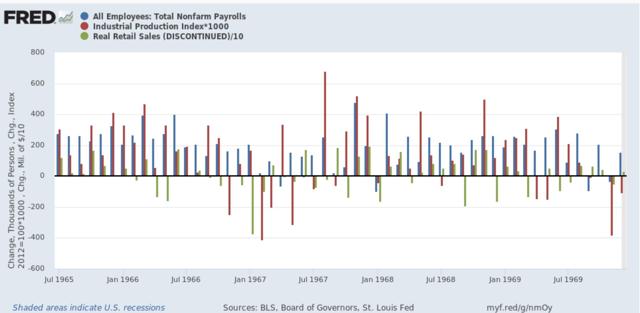

Following the inversion in 1966, the economy barely missed a recession, as payrolls, industrial production, and real retail sales all decline for several months or more in 1967:

Only real income continued to grow strongly, and real GDP only downshifted to near zero for one quarter in 1967.

And as I pointed out yesterday, the Fed lowered rates only 4 months after the inversion.

Meanwhile, virtually the last of the positive long leading indicators, corporate profits, finally get reported for Q4 next week. Earnings for the S&P 500 declined in Q4, and if corporate profits did too, then almost all of my long leading indicators will be flashing red.

Thursday, March 21, 2019

A couple of nuggets of good economic news

- by New Deal democrat

Sometimes there is almost no economic news at all. This isn’t one of those times.

Because there have been increasingly ominous signs among the long leading indicators, that have been spilling over into the short leading indicators, suddenly there are a lot of signs and portents to look at. A lot less about jobs and wages that I keep exclusively here.

So, once again I got waylaid preparing a long piece for Seeking Alpha, on how the Fed may need to *cut* rates quickly in order to avoid a recession, that may not get posted until tomorrow.

In the meantime, here are a couple of graphs to give you something to chew on.

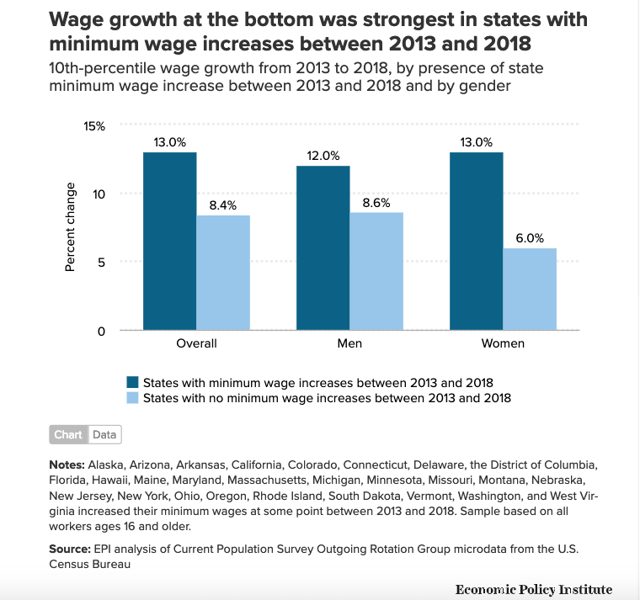

First, I’ve noted in the last few months how wages for ordinary workers have started to take off. A few people have pointed out that it may be less due to overall tightness in the labor market and more due to statutory minimum wage increases.

It looks like they’ve got a good point. Here’s a graph of wage growth for low wage workers in states that have raised the minimum wage vs. those that have not:

Pretty self-explanatory.

Second, recently the number of initial jobless claims has risen somewhat. The good news is, that number has backed off from the spike that occurred during the government shutdown:

The four week moving average of initial claims, at 225,000, is only about 9% above its low point 6 months ago. That does show some weakness, but not enough to warrant even a yellow caution flag at this point.

Wednesday, March 20, 2019

The widened Panama Canal is disrupting internal US transportation patterns

- by New Deal democrat

The newly-widened Panama Canal opened to traffic in late 2016. Since then, there have been several ongoing disruptions in how goods are transported from suppliers in Asia to their ultimate markets in the US, including affects on seaports, trucking, and rail.

This post is up at Seeking Alpha. As usual, clicking over and reading should be educational for you, and helps reward me for my work.

Tuesday, March 19, 2019

Over 50% of all wealth in the US is inherited not earned

- by New Deal democrat

I got waylaid putting together a very detailed post about how the newly-widened Panama Canal is disrupting the internal US transportation network. When it goes up at Seeking Alpha, I’ll link to it.

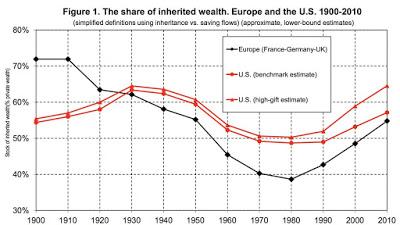

In the meantime, here is something that I found a week or two ago for you to chew on. Over half of all US wealth is not earned but inherited:

It’s likely that about 25% of all wealth in the US is inherited of the top 1%. I strongly suspect the relationship is even more egregious at the level of the top 0.1% and top 0.01%.

It’s hard to argue that the US is at all a meritocracy when the starting points are so distorted.

Monday, March 18, 2019

The government shutdown may have caused a mini-recession

- by New Deal democrat

Aside from being a monumentally poor policy outcome, and aside from the hardship it caused nearly a million workers, the government shutdown may also have caused a general contraction in production, sales, and income, and a slowdown in employment, that if it were longer would qualify as a recession.

Because the affected three months straddle Q4 2018 and Q1 2019, both quarters will likely show positive real GDP growth, it won’t be a recession. Let’s call it a mini-recession.

Although shorthand for a recession is two quarters of GDP contraction, that wasn’t the case for 2001, and the NBER has indicated that a general downturn in production, employment, sales, and income are the crucial criteria. So let’s look at each.

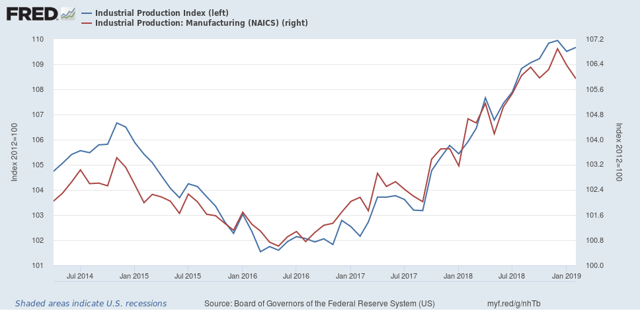

Industrial production declined significantly in December, and the small rebound in January was not enough to overcome that downturn. This is especially true of the manufacturing component:

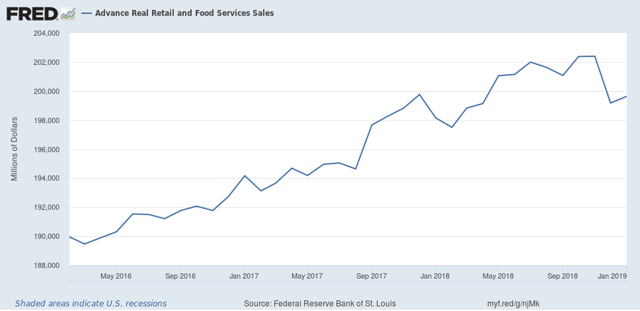

The same is also true of real retail sales:

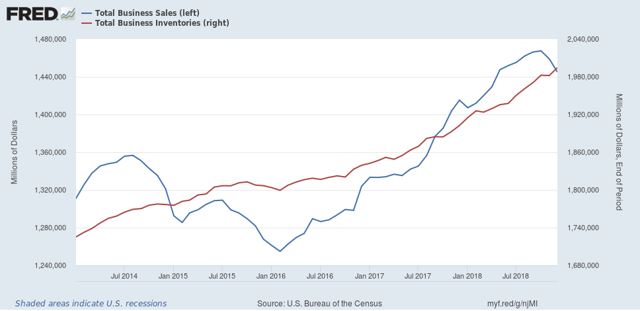

But lest you think that retail sales were an outlier, here are general business sales (including manufacturers’ and wholesalers’ sales)(BLUE) which also peaked in November, and inventories (red):

I included both because sales lead inventories, as is shown for the 2015-16 “shallow industrial recession” in the graph.

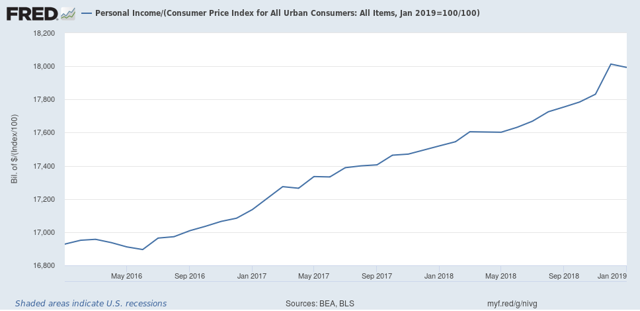

The NBER pays attention to “real personal income less transfer payments.” Since we don’t have the deflator for January, nor the amount of transfer payments, I am making use of CPI as a placeholder for the deflator:

These increased strongly in December, but declined in January.

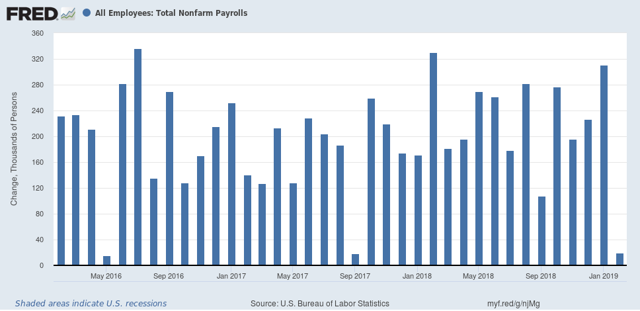

Finally, here is employment:

No decline here, but one of the three lowest monthly readings in February. And of course, this is well within the range of being revised to a negative over the next several months.

Put the four series together, and you get a picture of an economy that in terms of production, employment, income, and sales suddenly contracted in December and January.

Assuming these series bounce back no later than March - which I expect to happen - the downturn isn’t deep enough nor long enough to qualify as a recession. But the government shutdown may have done significantly more damage than was projected at the time. And this highlights how poor pubic policy, whether it comes from the Fed, the Congress, or the Administration, can very quickly topple a slowing economy into outright recession.

Sunday, March 17, 2019

Preventing Presidential autocracy: thoughts on reining in Executive power

- by New Deal democrat

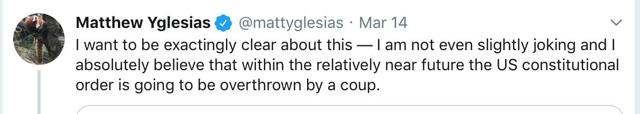

Matt Yglesias posted a jarring tweet this past week when he wrote:

He elaborated by linking to a long-form article he wrote four years ago, explaining his position, where in relevant part, he wrote:

America's constitutional democracy is going to collapse.

Some day ... there is going to be a collapse of the legal and political order and its replacement by something else. If we're lucky, it won't be violent. If we're very lucky, it will lead us to tackle the underlying problems and result in a better, more robust, political system. If we're less lucky, well, then, something worse will happen.

....

In a 1990 essay, the late Yale political scientist Juan Linz observed that "aside from the United States, only Chile has managed a century and a half of relatively undisturbed constitutional continuity under presidential government — but Chilean democracy broke down in the 1970s."

Yglesias — and Linz — saved me a lot of work. Because I had long ago heard that the US was the only Presidential democracy that hadn’t succumbed to autocratic rule. That was precisely Linz’s finding. At this point the only other democracies that I know of that come close are Costa Rica (since the last coup of 1948) and the Fourth and Fifth French Republics (since 1945).

Historically, the problem has been that, over time, in any Presidential system, the President accretes more and more power (vs. a corrupt, ineffective, and/or deadlocked Legislature) until the Legislature degenerates into a toothless rubber-stamp, or else is disbanded by a President turned autocrat.

The US has not been immune. The first six Presidents, through John Quincy Adams, saw themselves as “Chief Magistrates,” only vetoing laws they thought were unconstitutional, and at least approximating a meritocracy in their limited number of appointments. That began to change with Andrew Jackson, who vetoed any legislation that did not exactly conform to his wishes, and initiated the “spoils system” of appointing only political backers to government posts.

With the vast expansion of the bureaucracy during the 20th Century, Presidents obtained much more power via all of the appointments they were able to make. And following the Second World War, the large and permanent global military footprint enabled lots of chances for the Commander in Chief to flex his muscle.

Now we are getting very close to the final crossroads. Obama committed troops to Syria after the Congress completely gave up their war-making authority, preferring to sit on the sidelines and snipe. Trump’s declaration of an emergency simply because he could not get what he wanted out of Congress, if upheld by the Supreme Court, all but ensures that government by Executive Decree, that can only be overruled by a 2/3’s majority of both Houses of Congress, will probably quite soon become the norm.

In fact, Trump’s refusal of the GOP’s compromise proposal is almost certainly because, now that he has found this powerful new toy, he intends to use it more.

In fact, Trump’s refusal of the GOP’s compromise proposal is almost certainly because, now that he has found this powerful new toy, he intends to use it more.

Once Presidential Emergency Edicts become more routine, unless this or any future President’s party fails to seat at least 1/3 + 1 in both Houses of Congress, why even bother convening?

The bottom line is, I agree with Yglesias. We are on the way to autocratic Presidential rule unless the power of the Presidency is definitively reined in.

So, how should the Executive be reined in? Obviously, this must be via Constitutional changes. Below are my considered opinions for how to do that.

The mixed Presidential-parliamentary system used, for example, in France, in which some Executive powers are vested in a “Premier” or “Prime Minister” who is a member of the Legislature seem to be the best remedy. In the US, there are seven Presidential powers that ought to be either limited, or devolved in whole or in part to the Congress or its Legislative head:

The mixed Presidential-parliamentary system used, for example, in France, in which some Executive powers are vested in a “Premier” or “Prime Minister” who is a member of the Legislature seem to be the best remedy. In the US, there are seven Presidential powers that ought to be either limited, or devolved in whole or in part to the Congress or its Legislative head:

1. Appointment of rule-making authorities in the bureaucracy (vs. adjudicating authorities, whose appointments would remain with the President). For example, the SEC both makes rules for corporate governance, and enforces those rules. The President ought to be completely taken out of the former, Legislative, role. Those regulators should be appointed solely by Congress.

2. Aside from full declaration of war, or the need for an emergency response, devolution of the authority for taking of limited military action. Thus, for example, if the Congress were to refuse to declare war, then any commitment of troops to Syria would be the sole authority of the Legislative head. (This would make Congress far more responsive to popular skepticism of any such adventure). This is in accord with the manifest intention of the Consitution originally, in which *all* types of hostilities, including limited ones such as a “Writ of Reprisal” were vested in the Congress.

3. The 2/3’s majority requirement to overcome a veto gives the President too much Legislative power. The requirement, if not outright eliminated, ought to be reduced to something like 60%. And in any case, a sustained veto should only delay implementation of a law duly passed by Congress for two years, so that whether the law should go forward or not becomes a campaign issue in the next Congressional elections.

4. The Legislative head should be able to be removed in a no-confidence vote just as in Parliamentary systems, although a majority negative vote in both Houses of Congress might be required.

5. Unless specifically embodied in the language of Treaties, the President should not be able to single-handedly terminate them (just as the President cannot unilaterally terminate laws with which he disagrees).

6. The President should not be able to pardon any member of his own Administration for any acts committed before or during that person’s service during the Administration, nor for any acts undertaken in support of the President, or in conspiracy with the President.

7. No emergency declared by any President should be allowed to last longer than the time necessary for Congress to convene and debate the alleged emergency, e.g., 60 days.

I know I’m just typing some words on a keyboard for a few readers. But the bottom line is, government by Presidential Edict looks like it is looming in our near future. Parliamentary democracies are far less susceptible to such autocratic power grabs than Presidential systems have been. Two hundred years of such history ought to be enough to learn the lesson. The remedy must be a clear circumscribing of Presidential authority, with an effective counterweight in the Congress.