Second point of order: I hate Blogger. There, I said it.

Okay, having gotten that out of the way, on to some data.

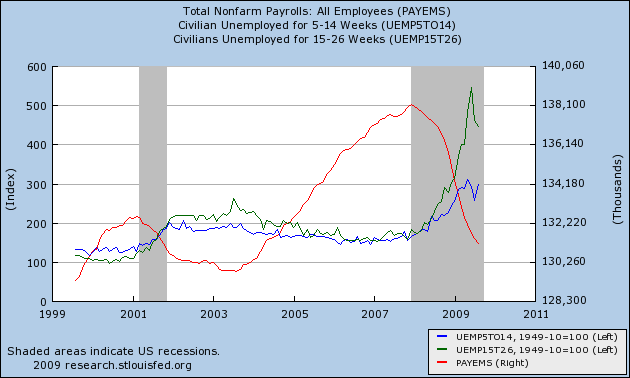

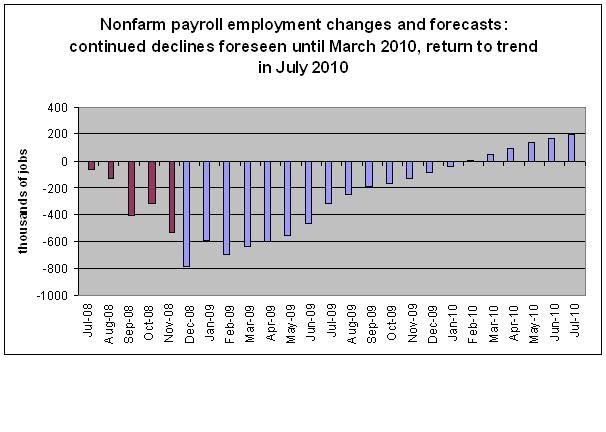

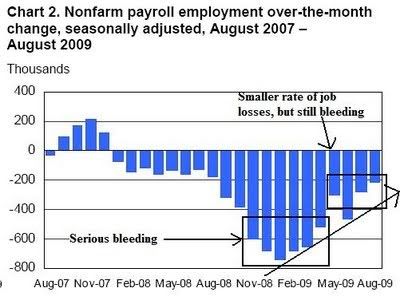

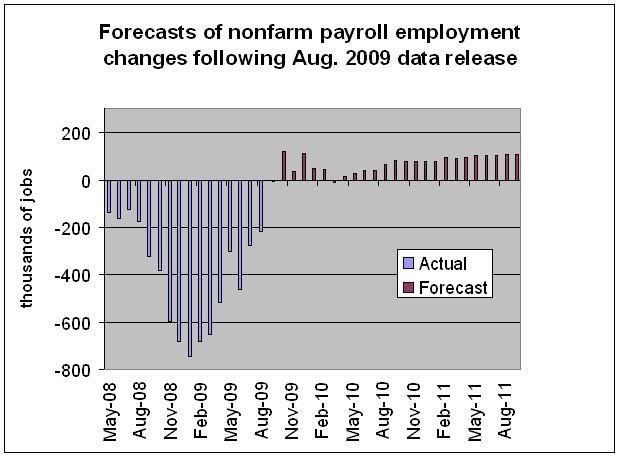

I’d be a fool not to acknowledge that most of the recent economic releases have been better than expected, particularly as relates to the most of the headline numbers. However, I’m still not sold on the sustainability, and in some cases I don’t necessarily like what I see lurking beneath the surface. I continue to believe that when it comes time for the government to hand-off the spending baton to the American consumer, the transition might not go as smoothly as everyone seems to think it will.

One of the favorite ratios I like to pull out of the Fed’s quarterly Flow of Funds report (released on the 17th) is the debt-to-income ratio of U.S. households.

Here’s what that looks like (click for larger images):

Our liabilities are currently just over $14 trillion while our income is just shy of $11 trillion; we’re at 129% debt-to-income, to be precise. The good news is that we’re down from 136% in the first quarter of 2008. The bad news is that to get to “trend,” or about 114%, we need to shed another $1.6 trillion, and a reversion to the mean, 77%, implies retiring about $5.7 trillion. Consider that in six quarters we’ve only paid down $350 or so billion and you can see this will be a long slog.

Complicating the problem is that the denominator in the chart above – Personal Disposable Income – is negative year over year for the first time in the history of the series:

The good news out of the Flow of Funds report was that Americans’ net worth went up in the quarter by $2 trillion, from about $51 trillion to about $53 trillion. The bad news is that we’re still down about $12 trillion from our $65 trillion dollar peak. Other good news was that real estate owners’ equity rose a bit, from about series low 41% to 43% -- but that number has a long way to go on the upside to be where it belongs.

We know the consumer is still overleveraged. We also know that the consumer has, for several years, represented about 71% of our GDP through Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE), or about $10 trillion dollars of our $14 trillion dollar economy. If the consumer were to pull back to the mean, say about 65% of GDP, that would imply a spending cutback of about $850 billion dollars. Some of that will no doubt be offset by the stimulus money, some no doubt by exports, some by inventory restocking. But it’s a big number nonetheless.

On other topics, BLS released state-by-state unemployment numbers last week, and it didn’t look too pretty: 27 states saw continued increases, with California hitting a record 12% and Michigan topping 15%.

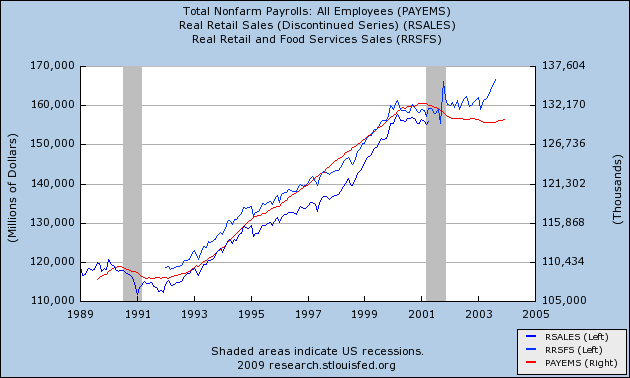

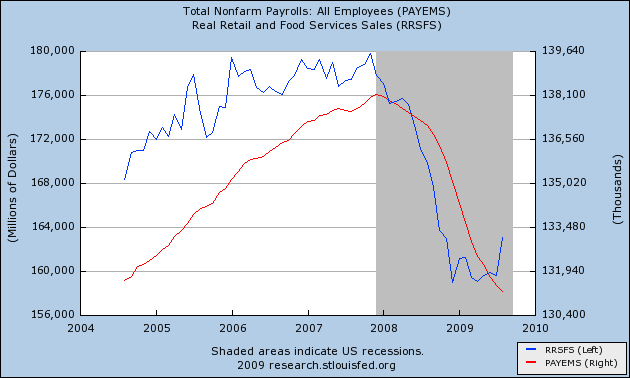

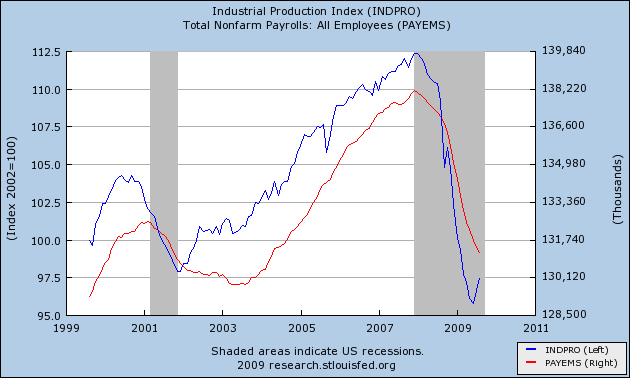

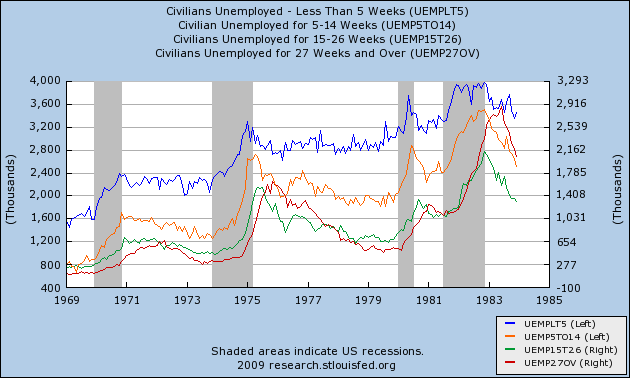

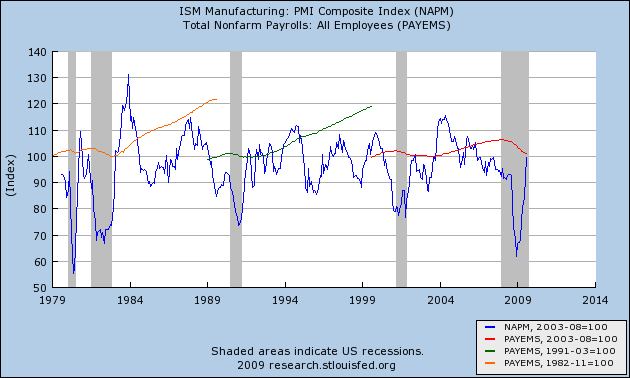

I’d posted elsewhere about how the 55+ age cohort is crowding out younger job-seekers, and I really don’t like the look of charts like this one:

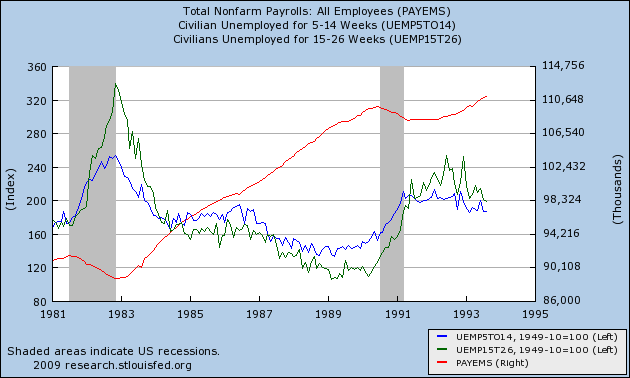

A chart like the one above leads in large part to one like the one below, where one might reasonably conclude that older workers are squeezing younger workers out of the workforce or, more accurately, probably preventing them from entering in the first place:

The stock market has, of course, shrugged off any notion whatsoever of double dippage and rallied along its merry way to a 60% or so gain off the March lows. I’d be lying if I didn’t say I think the market is now priced for perfection – through 2011 or thereabouts. But I learned the one key equation I needed to know early on in my career: Intellectually right + losing money = wrong. So I continue to look for signs of a top while simultaneously hoping that the economic fundamentals catch up to where the market thinks they are (or should be).

Lastly, I would note that 86% of Americans recently polled believe the country is still in recession. This is the point that many are trying to get across: While the country may have already "technically" exited recession -- or may be on the very cusp of doing so -- it is going to matter very little to the vast majority of Americans.

More thoughts on the Flow of Funds and perhaps some other stream of consciousness as time allows, which, regrettably, it rarely does.