The markets are closed (thank god, right?). So it's time to forget about the markets for the rest of the day.

The financial turmoil is taking on a new dimension: Banks that lent money to hedge funds and other big risk-takers are asking for some of it back.

Loans from banks and brokerages had allowed hedge funds, which manage some $1.9 trillion in clients' money, to amass many times that amount in investments. But as the value of mortgage-backed bonds and other investments has dropped in recent weeks, the lenders are demanding that borrowers put up more cash or assets.

This is producing a negative cycle that has policy makers deeply worried. When investors rush to dump assets, prices fall and lenders feel compelled to make further demands, or "margin calls," which cause even more selling.

So far, the turbulence touched off last summer hasn't resulted in many big hedge-fund blowups. If that changes, banks and other financial firms could end up holding even more hard-to-sell securities. Already, their troubled investments, especially in securities tied to mortgages, have cost them some $140 billion in write-downs.

.....

The funds facing the greatest pressure are those that are highly leveraged, meaning they have large borrowings relative to the money entrusted to them. Carlyle Capital managed only $670 million in client money, but used borrowing to boost its portfolio of bonds to $21.7 billion, meaning it was about 32 times leveraged.

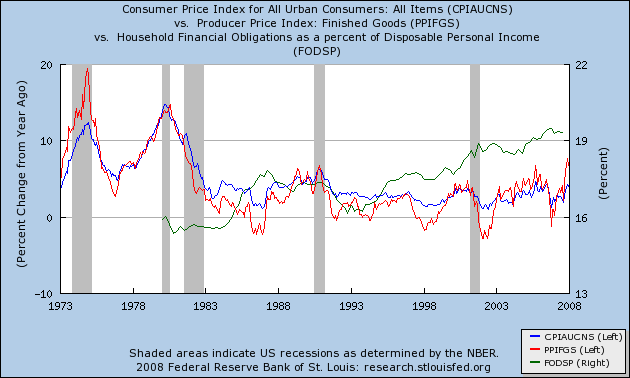

Below is a graph showing how inflation tends to play out over economic cycles. The blue line is consumer inflation (cpi). The red line is producer inflation (ppi) which is the rate at which costs are increasing to producers. The green line is household debt.

A regular pattern of cpi vs. ppi inflation unfolds over economic cycles. Consumer inflation is relatively tame, but consumer inflation starts out very low, and considerably less than consumer inflation (the red line is under the blue line). Simply put, producer costs aren't rising as fast as consumer prices can be increased, and increased production and sales leads to increased profits. Over time, both consumer and producer inflation increases. Ultimately, producer prices increase faster than consumer prices.(the red line is over the blue line). Producers aren't able to pass on their increased costs to consumers, and their profits decline. When their profits decline, they cut back and lay off employees. A recession ensues as consumers pull in their belts. Prices, especially producer prices, decline, thus setting off the next cycle.

In the graph above, you can see that just before every single recession, both the red and blue lines are going up, and the red line has overtaken the blue line. In other words, producer prices are rising, and have overtaken consumer prices. When the recession hits (the shaded area) both the red and blue lines decline, meaning that both consumer and producer inflation are decreasing.

Even as financial firefighters try to douse the flames, the search is under way for the cause of the fire.

How could a mortgage-market meltdown -- losses of perhaps $400 billion, less than 2% of the overall value of the stock market -- cause so much of a disturbance and do so much damage to the U.S. economy? "After all," Federal Reserve governor Frederic Mishkin observed last week, "a 2% decline in stock-market prices sometimes happens on a daily basis, and yet leads to hardly a ripple in the U.S. economy."

And is the fire being fanned by the way commercial banks are required to keep their books and decide how much capital to hold as a cushion against bad times?

The short answer to the first question is leverage. The short answer to the second is yes.

What role do you think leverage and the way banks decide how much capital to hold played in creating the current credit mess? Readers, weigh in.

Leverage is borrowing money to make bigger bets. Invest $1, borrow $9, buy something for $10. If its value rises $2, you've tripled your initial investment. It works great when the market is on the way up. On the way down, it amplifies losses.

.....

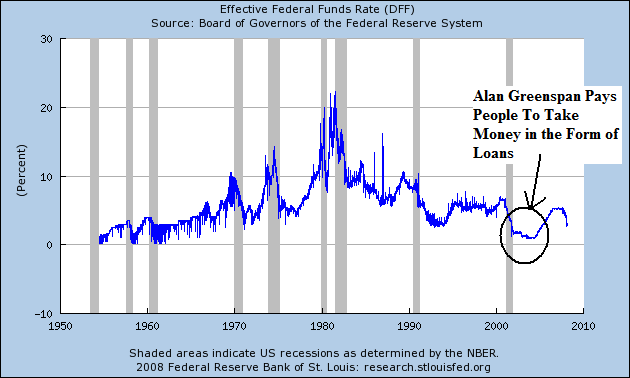

With money cheap, banks gorged themselves with leverage in good times, making not only risky mortgages, but increasing leverage by investing in securities that rested on the riskiest slice of those mortgages. Bank balance sheets now are on a forced diet.

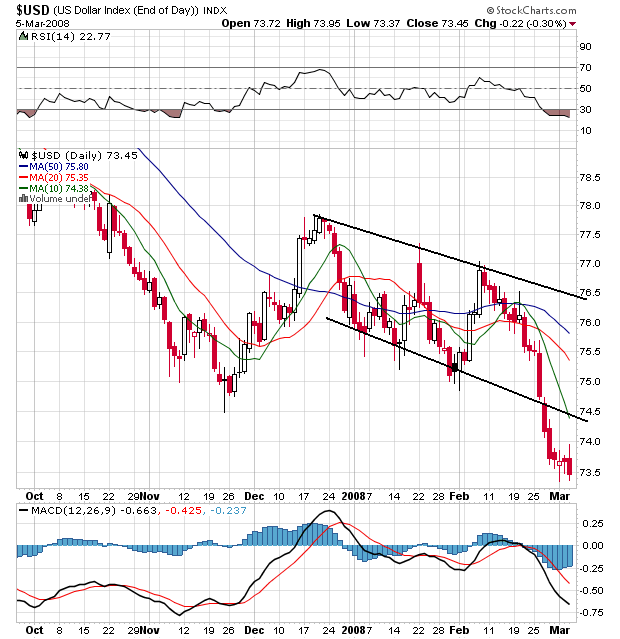

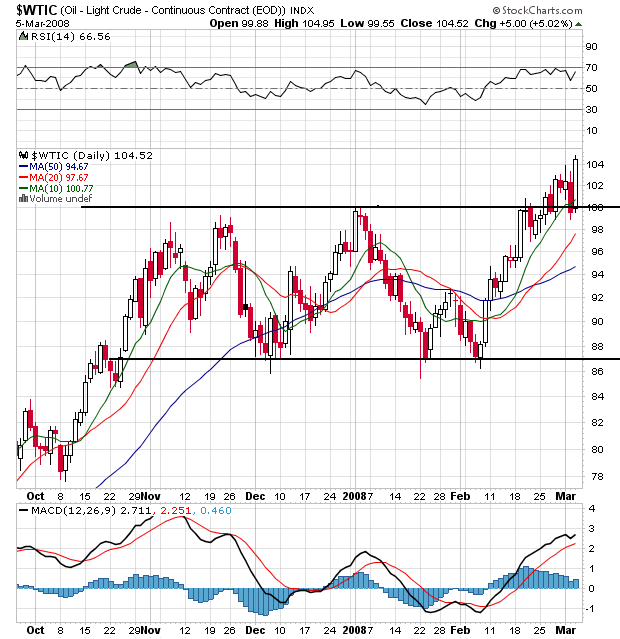

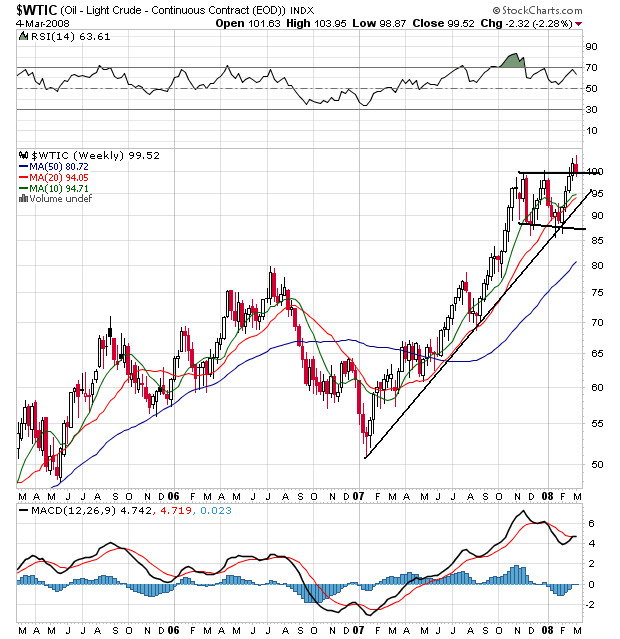

Ministers from the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, meeting in Vienna, blamed surging oil prices on the weak U.S. dollar and "mismanagement" of the U.S. economy. President Bush shot back, telling a renewable-energy conference in Washington that "it should be obvious to all that the demand [for oil] is outstripping supply." The U.S., he said, must change its habits. "We've got to get off oil," he said.

Mr. Bush urged OPEC this week to pump more oil. The cartel supplies just less than 40% of world demand.

OPEC ministers said they see a well-supplied market. OPEC President Chakib Khelil said the oil market is "moving into a new phase" of slower economic growth and ebbing demand.

With oil prices hovering near record highs and inventories flush, OPEC ministers meeting in Vienna today are all but sure to leave output unchanged. But with so much uncertainty facing the market, the group is likely to meet again in the next few months, amid deep-seated concern about the direction the global economy is taking and the implications for oil demand.

The 13-member Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, which supplies 40% of the world's crude, faces a tough dilemma. Were it to cut production at a time of high prices, it could get the blame if the world tips into recession. If it raises output as demand weakens, prices could nose-dive, threatening the group's revenue.

The U.S. made a last-ditch appeal to the cartel to raise output. President Bush said it was a "mistake" to have your biggest customers' economies slowing down because of high crude prices, which he warned could cause people "to buy less energy over time." The U.S. Energy Information Agency said OPEC should raise oil-production levels by between 300,000 and 500,000 barrels per day.

Oil rose nearly 20% in less than one month and trading has been volatile after OPEC signaled it would keep output unchanged. Krista Nonnenmacher, an independent market maker with AMEX, discusses the oil market and geo-political influences.

But the group is likely to sit on its hands. "It seems like there will be no change," Iran's oil minister, Gholam Hussein Nozari, said yesterday after a meeting of the committee that recommends policy decisions to OPEC.

A top Federal Reserve official said the central bank failed to fully appreciate risks that financial institutions were taking before the recent credit problems, and it is reviewing its regulations.

During a sometimes-contentious Senate hearing, Fed Vice Chairman Donald Kohn said the central bank is likely to become "more forceful" with the financial institutions it supervises. Mr. Kohn didn't explain what new actions the Fed might take, but he did warn banks to rely less on the assessments of credit-rating agencies.

After years of watching the banking industry make record profits, regulators are now scrambling to deal with turmoil stemming from problems in the U.S. housing market. Large U.S. banks have had to write down the value of assets by billions of dollars, including slivers of mortgage-backed debt that many believed were almost risk-free.

Mr. Kohn's comments mark one of the few times that a top Fed official has acknowledged shortcomings in regulation as a cause of the mess.

"I don't know that we fully appreciated all the risks out there," he told the Senate Banking Committee. "I'm not sure anybody did, to be perfectly honest." Later, he said the Fed "did not perform flawlessly -- I absolutely agree with that."

Edward M. Gramlich, a Federal Reserve governor who died in September, warned nearly seven years ago that a fast-growing new breed of lenders was luring many people into risky mortgages they could not afford.

But when Mr. Gramlich privately urged Fed examiners to investigate mortgage lenders affiliated with national banks, he was rebuffed by Alan Greenspan, the Fed chairman.

In 2001, a senior Treasury official, Sheila C. Bair, tried to persuade subprime lenders to adopt a code of “best practices” and to let outside monitors verify their compliance. None of the lenders would agree to the monitors, and many rejected the code itself. Even those who did adopt those practices, Ms. Bair recalled recently, soon let them slip.

And leaders of a housing advocacy group in California, meeting with Mr. Greenspan in 2004, warned that deception was increasing and unscrupulous practices were spreading.

John C. Gamboa and Robert L. Gnaizda of the Greenlining Institute implored Mr. Greenspan to use his bully pulpit and press for a voluntary code of conduct.

“He never gave us a good reason, but he didn’t want to do it,” Mr. Gnaizda said last week. “He just wasn’t interested.”

An examination of regulatory decisions shows that the Federal Reserve and other agencies waited until it was too late before trying to tame the industry’s excesses. Both the Fed and the Bush administration placed a higher priority on promoting “financial innovation” and what President Bush has called the “ownership society.”

On top of that, many Fed officials counted on the housing boom to prop up the economy after the stock market collapsed in 2000.

Mr. Greenspan, in an interview, vigorously defended his actions, saying the Fed was poorly equipped to investigate deceptive lending and that it was not to blame for the housing bubble and bust.

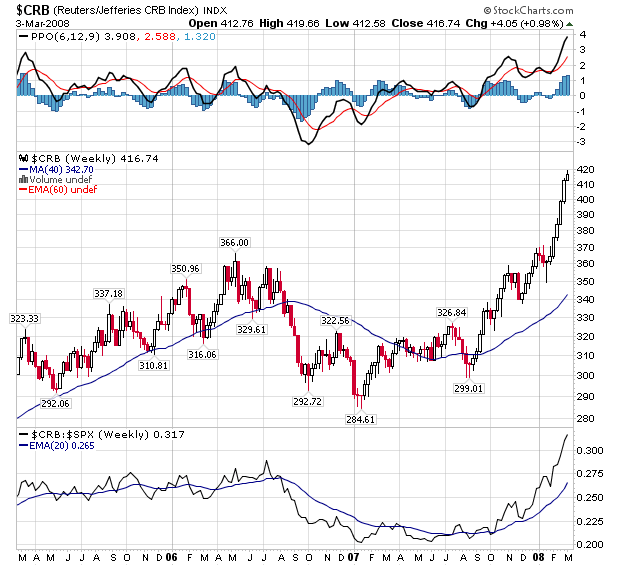

In nearly every recorded downturn, slower U.S. demand pulled the rug out from commodity prices. Over time, those cheaper prices for inputs like oil, copper and steel provided the needed push to get things roaring again.

This time, it's the opposite. Crude is beyond the $100 mark. Gold is near $1,000 an ounce, while silver broke above $20 for the first time in 27 years. Base metals like copper are red-hot dear.

Cocoa has flown to its highest spot in 24 years, coffee is at a 10-year peak and sugar is flirting with 18-month peaks.

Wheat prices have soared so high that Italy's government has warned its people to brace for big hikes in pasta prices. No kidding.

Thank China and other emerging markets for these sky-high prices, many experts say. So far, most of the U.S. slowdown is staying in the U.S. Construction abroad is booming and factories are humming. All of these efforts need energy and metals.

Wealth is growing where once there was just poverty. Those seeing some money for the first time in their lives are enjoying better diets.

The Chinese and others are buying more meat, sharply boosting demand for feeds like corn.

They also are driving gas-guzzling cars in ever greater numbers.

So, even as U.S. demand for most commodities is waning, total demand is rising.

"This is the China Syndrome," said Earl Sweet, senior economist at BMO Capital Markets in Toronto. "The U.S. economy is probably in a recession. And that normally would lead to weakening demand for all sorts of things."

"China accounts for 50% or more of the demand growth for copper, aluminum, zinc, lead and steel," said Mike Helmar, director of industry services at Moody's Economy.com.

Add to that India and smaller booming markets. That's where the new demand is coming from.

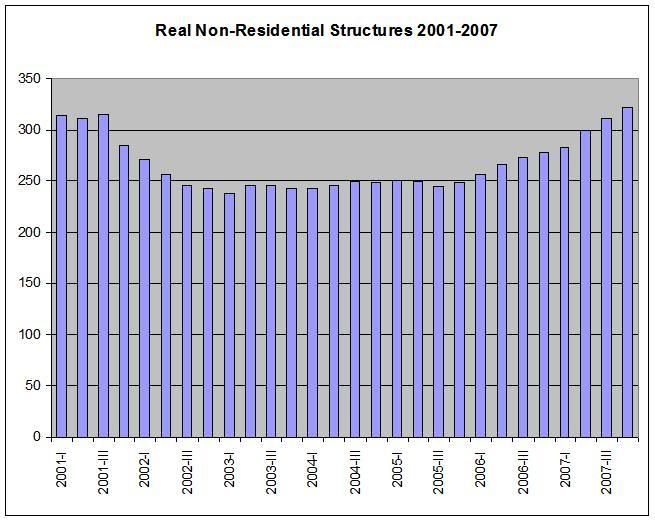

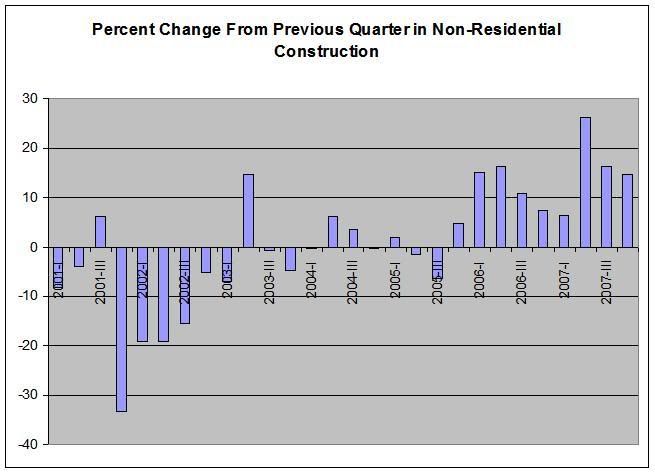

For the second month in a row, the Commerce Department reported a decline in spending on nonresidential construction -- which includes everything from hospitals to office parks to shopping malls. The report yesterday showed construction spending fell 1.7% in January from December, the steepest drop in 14 years. While residential construction accounted for a big part of the decline, spending on nonresidential construction slid 0.8%.

Meanwhile, there may be an oversupply of shopping malls and office buildings after a period of intensive construction. It adds up to bad news for employment, the economy and investors.

While the boom in commercial construction wasn't as dramatic as in home building, the impact of a slowdown on the economy could be significant. Nonresidential construction accounted for 3.6% of gross domestic product in the fourth quarter of 2007, up from 2.5% five years ago and the most since the second quarter of 1988, according to Moody's Economy.com.

As home construction got caught in a downward spiral last year, nonresidential construction continued to expand at a healthy clip. Spending on nonresidential structures rose 16% in 2007, the biggest four-quarter increase since 1984, according to Morgan Stanley.

Signs of trouble cropped up at the end of the year. As credit markets tightened, office space sold in the fourth quarter dropped 42% from a year earlier, and sales of large retail properties declined 31%, says Real Capital Analytics, a New York real-estate research group.

If spending continues to slow, construction workers, who are reeling from the housing slowdown, face more layoffs. Construction jobs made up 5.4% of nonfarm payrolls in January. While that's down from a peak of 5.7% in April 2006, it's still above the long-term average of 4.9%, say economists at Payden & Rygel in Los Angeles, leaving room for more job losses.